Arya Kshema Spring Dharma Teachings: 17th Gyalwang Karmapa on the 8th Karmapa Mikyö Dorje's Autobiographical Verses

25 March, 2022

After warmly greeting listeners, His Holiness continued his teaching of the Eighth Karmapa MIkyö Dorje’s Autobiographical Verses which he has based on Sangye Paldrup’s commentary. Previously His Holiness had discussed meditating on relative bodhicitta. This has two parts:

- Exchanging himself for others in meditation

- Taking adversity as the path in post-meditation

The latter is further divided into ten sub-sections. His Holiness had spoken of the first, “taking running out of supplies as the path”, on Day 3. Today, he gave a presentation of the second sub-section, “taking harm as the path”.

Taking harm as the path

Of the thirty-three good deeds described in the Autobiographical Verses, this is the twelfth. Mikyö Dorje wrote,

When others unreasonably repaid kindness with harm,

I’d think, “May the results all ripen on me,

To never be experienced by this person,”

And dedicated all the virtue to them.

I think of this as one of my good deeds.

When many of us think about the era during which Mikyö Dorje lived, we believe it to be a fortunate time with fewer conflicts and strife than the present day. We believe that people of Mikyö Dorje’s time had great faith in and devotion to the gurus, and thus they would not criticize dharma teachers. However, through examining Mikyö Dorje’s life, we see that this was not the case. During his early life, there was dispute about whether Mikyö Dorje was really the Karmapa or not, and there were conflicts within the Karma Kamtsang tradition as well as between schools. In addition, Mikyö Dorje took care of many people, giving them food, supplies, wealth, and kindness but he was sometimes falsely accused and was met with unwarranted hostility. People from both inside and outside his tradition tried to create obstacles to his activity of spreading the Dharma.

How did he face these obstacles? It is as he said in his own Instructions of Training in the Liberation Story of Mikyö Dorje,

When these external and internal maras caused such harms, it is because of accumulating the karma of causing them harm and the afflictions from beginningless samsara that in this lifetime they caused harm. Otherwise there would be no basis or cause for them to harm you and it would have been impossible for them to cause you harm. For this reason, one thing we must pay attention to is that we must continue to strive to purify our own being of the bad karma that will ripen upon rebirth and that is certain to be experienced, and the obscurations that prevent higher states and true excellence.

If we follow Mikyö Dorje’s instructions, in cases such as these, we should turn our attention inwards and put effort into cleansing our obscurations, such that we do not continue to harm others and such that we end this ongoing spinning of the wheel of harm and suffering. No matter how much harm others cause us while we’re on the path trying to bring benefit to beings, we need to see this as a way of accumulating merit for both the bodhisattva and the mara (those who cause obstacles to spreading the dharma or those who cause harm). If it becomes a way of accumulating merit and becomes a cause for achieving enlightenment, we have changed a bad condition into a good condition and a good cause. In turn, we will not be harmed. For the other person, there will not be such a bad full ripening in the future that typically comes from harming others. We have to see how much we can train in the vast conduct of the bodhisattva; this is the main point of what is said in the Instructions on Training in the Liberation Story of Mikyö Dorje.

Putting the instruction into practice: never losing a loving attitude

Ordinarily, people would give up on those who treated them wrongly but Mikyö Dorje never did. To those who repaid his kindness wrongly, he never thought, “They’ve done all of these bad things so therefore let them be sick,” or so forth. He never blamed them or said, “I helped you in this way in the past so why are you treating me like this now?” He never believed he was right while they were wrong or accused them of being bad people while asserting he was good.

Mikyö Dorje never blamed others after they mistreated him. In fact, he treated them with kindness and with a particular affection. He made aspirations such as, “May those who have been ungrateful to me not experience a bad ripening of karma,” and “Causing harm is a misdeed and the ripening of the misdeed can only be suffering. May that ripening of suffering not ripen on them but on me.” Another example was a man by the name of Lhatse: Mikyö Dorje sent him many gifts and treated him very well. However, Lhatse caused significant problems for Mikyö Dorje. When Mikyö Dorje heard that Lhatse had died a horrible death, he never thought, “He deserved it,” or ,“It served him right.” He took no joy or satisfaction from his death and never uttered insulting words at all. Rather, he said that Lhatse had had a hard time and was overcome and controlled by his afflictions. The Eighth Karmapa often thought about all those enshrouded by the darkness of delusion, burning with the fire of hatred, and enslaved by the afflictions, as they were accumulating bad karma. Mikyö Dorje’s attendant, Sangye Paldrup, recorded that Mikyö Dorje was really very anxious for them, as though his heart was pierced by a needle. He fretted for days, and he went to the Three Jewels and shed many tears.

Mikyö Dorje was not only a lama well-known for teaching the dharma, he was a worldly judge as well, with great influence throughout Tibet. Thus, in addition to having spiritual authority, he was given secular authority. He could have had all those who did not listen to him, were proud or acted wrongly punished, by way of fines, physical punishment or even execution. He could have fiercely upheld the law or had strict rules. Yet Mikyö Dorje did not act like this. He did not state, “This is the rule of the Encampment or the rule of the land.” Instead, he did not cause problems for wrongdoers or punish them because he did not want them to suffer or be unhappy. If he had an opportunity to talk to them, he would tell them to use the dharmic antidote of the Four Powers and confess, but even from the depths of his mind he would never feel any bias, attachment, or hatred towards any other sentient being. This shows he thought only of their needs and their feelings.

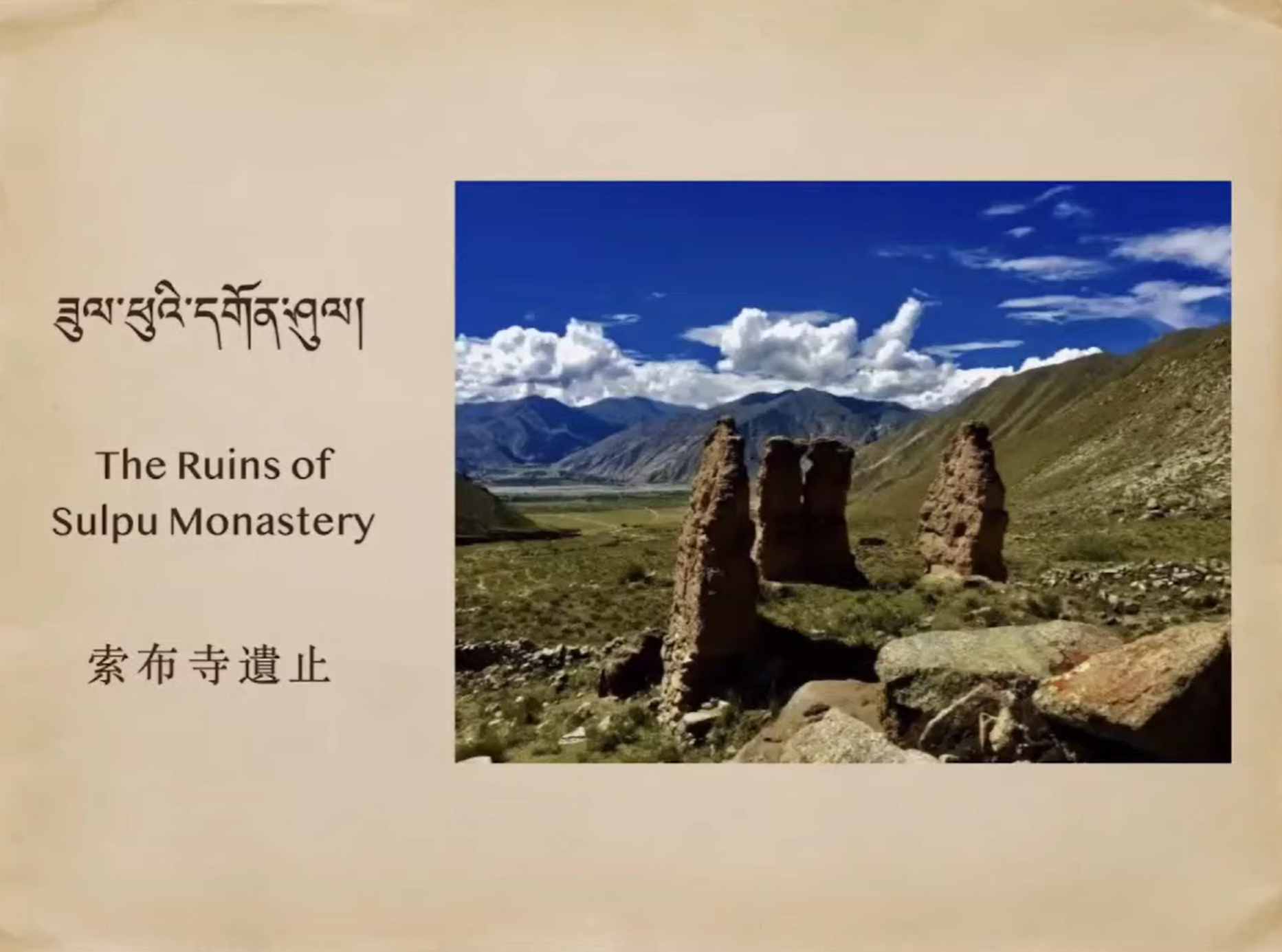

Without making any effort on his part, Mikyö Dorje’s merit and fame became widespread. As a result, some people from other schools and lineages grew jealous and annoyed by him. They accused and criticized him unjustly, and prevented the public from going to see him or having audiences with him. For example, in his mid-30s he was unable to travel to see the precious Jowo Shakyamuni statue in Lhasa because of grudges some people held towards him, which made it difficult for him to travel. Also, while in his 40s, an important king in Tibet named Lord Pakdru offered Mikyö Dorje Sulpu monastery in the region of Ü, which was one of the six important monasteries for the study of Buddhism during the reign of Je Tsongkhapa. Before showing a photograph of the monastery ruins, His Holiness explained that Mikyö Dorje did not want to be the administrator of the monastery. He did not believe it would work out. However, because of Lord Pakdru’s importance, he could not refuse the offer. Accusing Mikyö Dorje of being an emanation of a mara and of coming in to take away their place, sangha members of other traditions took up arms in order to stop Mikyö Dorje from entering their territory.

This demonstrates how Mikyö Dorje experienced difficulties and conflict during his lifetime, yet never lost his loving attitude towards those who had caused him harm. He even said that they should be offered sustenance and other goods.

We say the downtrodden worry about their own suffering but noble beings worry about others, as they know those people will experience suffering. We may wonder how beings can act in harmful ways. His Holiness explained that in this degenerate age, maras, ghosts and spirits who don’t like the dharma can have a great influence on others and change the way people are thinking and acting such that they do harm. His Holiness explained that we may not be able to see these spirits and maras with our eyes but they do try to change especially powerful and influential people. Controlled by their karma and their afflictions, they can’t be blamed for their actions.

Mikyö Dorje thought about this extensively. Instead of blaming others for treating him badly, he did everything he could to stop their afflictions. If he couldn’t stop the afflictions, he tried using skillful means to stop their harmful actions. For example, he avoided going to places where he would have many students or receive many offerings and went instead to isolated areas. He prayed that the karmic effects of bad actions would ripen on him and the results of his pure actions would ripen on others, and he dedicated his virtue to evil beings that were threatening or harming him. MIkyö Dorje wrote that this was one of his good deeds.

The shared characteristics of the Liberation Stories of the Karmapas

His Holiness shared his motivation for teaching the Liberation Stories of the Gyalwang Karmapas. He asserted that, as an ordinary sentient being who is controlled by the three afflictions, when he is teaching and speaking about liberation stories, he thinks about being a follower of the Gyalwang Karmapas and of Buddhism. Following the path of the body, speech and mind of the Gyalwang Karmapas entails, for him, studying their liberation stories and doing as much as he can to practice them. This is a motivation we should all share.

There are four shared characteristics found in the liberation stories His Holiness chose to discuss during today’s session. First, all of the Karmapa incarnations have been skilled, hard-working dharma leaders who have used many methods to spread the dharma to many places. Many Karmapas never stayed in one place but rather travelled to remote areas and to many regions throughout Tibet, China, and Mongolia. As a result, they gave many people opportunities to see them and hear them teach, and developed deep connections with people in different areas. Even today, in some regions where there is no Kagyu monastery or Kagyu monastic, many households have an ancestral tradition of chanting “Karmapa khyenno”. This shows the deep imprint made when past Karmapas travelled to those particular areas and forged connections with the local people. We can ascertain from this that past Gyalwang Karmapas spread the Dharma to many areas of Tibet and worked hard to bring benefit to the region.

The second characteristic discussed is that each Karmapa had his own individual character and style and brought his own ideas to the tradition. As such, the Karmapa tradition was not just old, ossified and dogmatic. Some Karmapas were wrathful while others were more peaceful. They had diverse interests. Mikyö Dorje, for example, really enjoyed studying and discussing texts with others, and he liked statues and other representations of Body, Speech, and Mind. In addition, he had a recognizable writing style. It is said that Gendun Chophel’s Ornament of Nagarjuna’s Thought was influenced by Mikyö Dorje’s style as seen in his Chariot of the Practice Siddhas. On the other hand, the Tenth Karmapa, Chöying Dorje, had a great interest in art and his own particular artistic style. We can say that the Karmapas not only helped to spread the Dharma, but were broadminded and had different areas of knowledge.

Third, none of the Karmapas has liked having power and influence. This does not just refer to political power; they did not much care for administering monasteries such as Tsurphu and did not care to maintain the status of “Karmapa” either. The liberation stories of the Eighth and the Ninth Karmapa state that they preferred to go to remote places and did little to maintain the Encampment.

The fourth and last characteristic is that the Karmapas rejected sectarianism and maintained a broader view of benefiting all of Tibet. Although we say that their main activity and responsibility has been to uphold the Kagyu lineage, in the Bright Lamp of the Teachings by the Fourteenth Ganden Tripa Rinchen Öser, it is said, “The Karmapas are revered in common everywhere throughout China and Tibet.” If you look at the activity of the Karmapas up until the Tenth Karmapa, you can see how they had the great broadminded view to teach all Tibetans and all schools in general. They did not identify the Kagyu lineage alone as being correct. Instead, they saw the reasons for having different schools, regarding them and the Bön tradition favourably. The Karmapas unilaterally rejected sectarianism and bias towards the various schools and lineages. For this reason, Patsap Lotsawa gave the First Karmapa Dusum Khyenpa two sacred objects––a painting showing all of the upholders of the Buddha’s teachings from the Buddha Shakyamuni to Bhikshu Simha and a conch said to be from Bodhgaya from the time of Nagarjuna. Giving these sacred objects to the First Karmapa, Patsap Lotsawa told him, “I am transmitting the Buddha’s teachings to you, so you must take the responsibility for teaching the entire teachings of the Buddha.”

Similarly the Second Karmapa Mahasiddha Karma Pakshi had no sectarianism or bias for any sentient being or school. He compared his inclusive view to the sun shining in the sky:

Like the sun in the sky,

May the being Rangjung Dorje

Have nonsectarian auspiciousness.

Through the activity of a bodhisattva,

May the light of his compassion shine

In all directions like the full moon.

May there be the auspiciousness

Of happiness in the world.

Bodhicitta is having no bias toward any sentient being, whether they be close or far, which can be compared to the light of the moon that shines on all sentient beings without dividing them into factions or sects. The activity of the bodhisattva is like the light of compassion, shining in all directions without any bias, and their sole wish is that there may be “the auspiciousness of happiness in the world”.

Documents of the Third Karmapa Rangjung Dorje and the Fifth Karmapa Deshin Shekpa say that theirs is not a lineage of Indian Kings nor of Chinese emperors. Theirs is a lineage that upholds the Buddha’s teachings, that is to say it is not sectarian.

The Seventh Karmapa Chödrak Gyatso likewise wrote,

Here in Tibet, all lineages are primarily only Buddhist, Mahayana, and in particular Secret Mantra teachings. There is no discordance within the teachings taught by the Buddha. The current separate lineages of the Sakya, Jonang, Shaluwa, Bodongpa, Gelukpa, Radreng or Kadampa, Sangpuwa, Gampopa, Tsurphupa, Drikung, Taklung, Drukpa, and so forth do not mean individual dharma lineages. They are distinct traditions of daily prayers and hats in different regions and customs due to the development of monasteries. Not being the same in those ways does not mean that the teachings of the Buddha are different. All of them are solely pure teachings of the Buddha, so they are proven to be true recipients of offerings to gather the accumulation of merit.

Here, the Seventh Karmapa is emphasizing that, although there are many different lineages, we are the same in being practitioners of the Buddha’s teachings. There is harmony amongst us regardless of whether we are practicing the teachings of the Sakya, Gelug, Foundational, Mahayana, Secret Mantrayana traditions and so forth. We are divided into different lineages, we have different names, different monasteries were founded, we wear different hats or ring our bells in puja slightly differently, but in actuality, we are all the same. The minor differences in external form do not make an actual difference because we are all the same in being practitioners of the teachings of the Buddha.

In his Letter to be Announced in all Kingdoms, the Seventh Karmapa also wrote,

As the Karmapa, I do not distinguish between any factions in places, communities, students, teachings, dharma traditions, and so forth. I do not hold there to be a separate “Karmapa’s tradition” or “teaching.” The teachings of the Buddha are the teachings of the Karmapa. I take care of the teachings of the Buddha. All those who enter them enter the teachings of the Karmapa.

Although His Holiness did not discuss them at length here, he mentioned Mikyö Dorje’s Instructions for the Lord of Kurapa and his Nephews as additional relevant reading. In this text, Mikyö Dorje offers detailed reasons why having sectarian views about the Buddha’s teachings is not appropriate.

His Holiness then stressed one of the main points of the day’s teachings: the importance of assessing the situation in the world and seeing the harm of having biases. Normally, he said, we stay in our own monasteries that exist within specific dharma lineages. This shapes how we see things with our eyes and how we think about things with our mind. However, this may lead to our views being limited. We really only consider how our own monasteries and our own labrangs will flourish and we think our own monasteries need to remain forever. Consequently, we do not see others at all and we don’t see that things are changing. Thus, we need to begin thinking more profoundly, using our two eyes to examine ourselves rather than looking at others, His Holiness urged. He recommended trying to look at our lineage, our monasteries, and our labrang as though we were a person on the outside looking in. He then stated that we need to expand the range of where we’re looking so that gradually we can expand our viewpoints.

As we are now in the 21st century, we can no longer continue as we did before with our hands covering our eyes. Looking at the world, we see there are many, many religions, and many true religions among them. Christianity and Islam are the largest religions in the world and several countries identify as being Christian or Muslim. On the other hand, there are only a few Buddhist countries left in the world. Although Buddhism is considered to be one of the world’s major religions, if you compare its spread or dissemination to that of Christianity or Islam or other large religions, it is relatively small. Previously, there were many more Buddhist countries than there are now, and many of these countries have ceased to be Buddhist. This shows there has been a real decline in the Buddhist teachings.

Though there are some external factors contributing to Buddhism’s decline, such as conversion to other religions, His Holiness suggested that the most significant factor contributing to Buddhism’s decline is an internal condition, specifically the division and factionalism that exists between Buddhist communities. There are, in fact, very few good connections between Buddhists. This is something we need to consider seriously. We continue to make many different distinctions such as Foundational and Mahayana, or Sutrayana and Vajrayana. Likewise, we say Chinese Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, and Theravada Buddhism. Even within Tibet, there are five great lineages. Within the Kagyu there are dozens of traditions, with its elder and younger lineages and so on, there are many different divisions.

Originally, there were very few Buddhist lineages, His Holiness explained, but over time, they split into many smaller factions and became weaker and weaker. There is the danger that one day there won’t be anything left for anyone to see. For that reason, among Buddhists, in Tibetan Buddhism, and in the Kagyu lineage, we shouldn’t have this sectarianism of saying “us” and “them”. Even making a distinction is not good because when you make distinctions, naturally you begin to have bias. We must take the first step ourselves; we must take action otherwise it’s like having a nice piece of fruit. You put it on a plate and leave it. What happens? It rots. We have to start with our own monasteries and lineages. We do so by increasing our ideas of creating connections and unity, and expanding our idea of belonging, until we reach the belief that we’re the same inside and out, and understand the unity of Buddhism. This really comes down to the idea that if one declines, we all decline; if one spreads, we all spread. Whether Buddhism declines or spreads therefore depends on this. Take the example of the United States. Because it is a powerful country, its citizens can hold their heads high and be confident anywhere as an American. If an entire country is not doing so well, its citizens will be weaker and have less confidence. It is difficult for us to develop this feeling when we stay within the environment of our own specific lineages.

People often fail to realize how very sacred it is to be in Buddhist monasteries in the presence of the sangha. But one day if you travel to Europe or a non-Buddhist country, you may not even find a statue of the Buddha, never mind there being Mahayana, Secret Mantrayana or disputes between Tibetan traditions. If you were to see a statue of the Buddha in such a place, you would be overjoyed! We take such things for granted, but in many countries around the world, there aren’t even any Buddhists, much less Kagyupas or Karma Kagyupas. Kagyupas are like rabbits with horns — they don’t exist! And yet many people sit in their monasteries thinking, “The sky is Kagyu, the earth is Kagyu, everything is Kagyu.” Thinking this way is no better than being the frog in the well, unable to see the external world or the overall situation.

Some monastics sit there thinking that nothing will change, but there has been a lot of change in the world already. We are becoming a single, global, human community with increasingly greater connections. In a time of such development, if we stay in our own little world covering our eyes, we’re just deceiving ourselves. We have to open our eyes.

In terms of being Buddhist and bringing benefit to the Buddhist teachings, we need to all respect one another and serve all in the same way. This is the foundation of being Buddhist; we need to take care of this great basis that we have. This means we can be a follower of the Buddha and practice the Dharma as it’s taught, that is to say not having any bias in the teachings or towards people, or having any notion of greater or lesser. We should not let the kindness of the great masters of the past, who upheld and spread the teachings with such great effort, go to waste.

The Karmapa clarified what it means to be non-sectarian. He emphasized that it does not mean not having our own standpoint or basis. We each have our particular karmic connections and the lineage we have entered because of them, so it is our particular responsibility to serve our own particular lineage. It is extremely important to respect that. Rather, being non-sectarian means considering other lineages as the same as, if not better than, our own. Even with the intention of preserving and spreading the Buddhist teachings throughout this world, if your thinking and outlook are old-fashioned, if you are unwilling to open your eyes and look at how the world is now, simply saying “I will spend innumerable eons achieving the state of Buddhahood” is merely an ensemble of words that you will be unable to accomplish. For these reasons, we need to train in the Liberation Stories of Mikyö Dorje and think about the faults that come from factionalism and bias.