Arya Kshema Spring Dharma Teachings:

17th Gyalwang Karmapa on The Life of the Eighth Karmapa Mikyö Dorje

February 27, 2021

The Karmapa began with advice for those in India and Nepal not to become too relaxed about the Covid 19 pandemic but to continue to be very careful and take precautions

Part 1: Deshin Shekpa Travels to China

According to the histories, the Ming emperor Yongle invited the Fifth Karmapa, Deshin Shekpa, from Ütsang [which is how the Chinese documents refer to Tibet] to perform rituals for the emperor’s deceased parents, a custom which is very important in Chinese culture. During the Karmapa’s visit, the emperor also had lengthy discussions with him on political strategies he should adopt in Tibet. The emperor hoped that, with his military backing, Deshin Shekpa would assume political power and responsibility in Tibet, in the same way that Drogön Chögyal Pakpa had done during the Mongol Yuan dynasty. Kublai Khan had given Drogön Chögyal Pakpa the title “Precious King of Dharma” and the Ming Emperor now gave that same rank and title, with just some minor differences, to Deshin Shekpa

Deshin Shekpa had no wish to accept any political power or responsibility and gave two reasons: sending a Chinese army into Tibet would only create turmoil and strife for the Tibetan people; and having many Dharma lineages in Tibet was beneficial. He requested instead that the Ming emperor give positions and titles to both secular and religious leaders of all traditions in Tibet. This the emperor did, and the Ming dynasty continued this tradition. After Deshin Shekpa returned to Tibet, the Ming emperor invited Je Tsongkhapa. Tsongkhapa, however, was unable to go, but the emperor likewise invited Jamchen Chöje of the Geluk order, Tekchen Chöje of the Sakya and so forth, giving them titles, just as he had given Deshin Shekpa.

While Deshin Shekpa was in Nanjing, he made many suggestions to the emperor, and consequently, the emperor granted amnesties to people in prison. This is evidence of Deshin Shekpa’s great loving-kindness towards sentient beings, which he showed in his acts many times. He also fulfilled a prediction made by the Fourth Karmapa, Rolpai Dorje. This said that if a pure bhikshu were to pass away on a certain mountain and his body were to be cremated, there, there would not be war between China and India. Eventually, Deshin Shekpa passed away on that very same mountain and his body was cremated there; because of which his successor was able to go to India and prevent the war between China and India. The Khenpo of Gendun Khang composed a praise which said that the incarnation of Rolpai Dorje would be able to protect many sentient beings from danger and bring them happiness. Knowing this, he would take rebirth intentionally - that was Deshin Shekpa.

On his return to Tibet, many people came to welcome him. Even Je Tsongkhapa sent him a letter, which is preserved in the Collected Short Works of Je Tsongkhapa. In this letter it says: “Regarding the person who takes responsibility for the teachings of the Buddha to flourish, there is no one greater than Deshin Shekpa, the Karmapa”. Along with the letter, he sent a statue of Buddha Shakyamuni sitting in the seated position of Maitreya from Reting monastery. The Sixteenth Karmapa brought the statue with him from Tibet and it is in the treasury at Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim. Masters from other traditions also wrote letters.

Tsurphu Jamyang Chenpo, a direct disciple of Deshin Shekpa, wrote a namthar which was unavailable before but which we do have now. In it, he states that during the time that Deshin Shekpa was in China, it was not only the high officials who came for an audience, but many people came who spoke various different languages. Thus, Deshin Shekpa would teach the Dharma surrounded by four or five translators. Many of the people who came for audience with Deshin Shekpa had travelled for days, prostrating with each step they took, as was the old Chinese tradition. Mainly, Deshin Shekpa taught reciting the name mantras of the buddhas and bodhisattvas and making commitments, such as giving up killing. Thus, he encouraged the people to practice virtue.

In the Chinese National Library’s collection, there is a text called The Names, Images and Name Mantras of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. It concerns the exchange between China and Tibet of Buddhist texts and printing techniques during the Ming period. [ His Holiness showed a slide of the book which has been published using these texts]. The text is primarily written in Chinese; there are some sections that include four alphabets including Lentsa, Tibetan, and Mongolian with Chinese introductions and conclusions. There are three sections that are primarily sections that give the images, names, and name mantras of buddhas and bodhisattvas in a mixture of Chinese and Tibetan. There is an image of Deshin Shekpa among them. It was printed in Beijing in 1431, the sixth year of the reign of Emperor Xuande, by Deshin Shekpa’s Chinese student Xiūjī shànzhu.

The foreword to this text, in Chinese and Tibetan, reads, “The Karmapa or Precious King of Dharma has shared many of the Dharmas and scriptures that he had given. So, these are now printed in this book.” Many researchers say this is an important text and is a good source regarding how Tibetan Buddhism spread to the East into the Chinese areas.

There is a similar text from the Ming dynasty called Sì Yǒu Zhāi Cóngshū which has the same meaning and the same influence as this text. The focus of this second text is Deshin Shekpa’s ceremonies for the emperor’s parents at the Linggu temple; there were different auspicious signs, divine music from the sky, and everyone saw and heard them. The witnesses reported what they had seen to the emperor, and the event was captured in a song entitled Auspicious Omens in the Sky. From that time on, the emperor’s faith in Deshin Shekpa became stronger and he studied the Buddhist scriptures even more assiduously than he had before. He also wrote Dharma melodies which were performed in song and dance in the palace. The emperor finished composing in the seventeenth year of his reign and printed everything in a book with some pictures of the Buddha. The book was distributed widely.

Then, on the 12th day of the 9th month, the emperor went to Dabaung monastery [which translates as” The Great Monastery of Repaying Kindness”]. He had the book reprinted and distributed. In the next year, on the 16th day of the 5th month, he asked for the two ministers to print and spread these texts with the names of the buddhas and bodhisattvas and melodies in the Shanxi and Henan regions. And so, the emperor’s mind moved into the direction of the Dharma. He had such a great interest in the Dharma; his queens also developed great respect for the buddhas and bodhisattvas. For the sake of all the people who had great faith in the Dharma, he built many monasteries inside and outside Nanjing and it was filled with temples.

His Holiness briefly explained what is meant by Dharma melodies. Karma Pakshi, wherever he went, would wear the black crown, and recite the mani mantra to a melody, and spread that practice. The later Karmapas continued this form of activity, wearing the black crown and reciting the melodies. During the time of the 16thKarmapa, however, when he wore the black crown, they would play the gyalings but not recite the melodies. Thus, at the time of the earlier Karmapas, people were primarily benefitted by the mani mantra and the mani melody which was sung at that time. When Deshin Shekpa performed the ceremonies and rituals, so many auspicious signs occurred, the people naturally developed faith and belief, and would recite the mani prayer day and night.

However, at some point there was some confusion in connection with the Ru-Shen clan who practiced Confucianism and were not in favor of Buddhism. They claimed that the mantra OM MANI PADME HUNG could not be translated into Chinese, and one should therefore recite AM BANI HUNG instead, which translates as “I am flattering you”.

What is the relationship between having faith in the Karmapa and reciting the six-syllable mani mantra? The Chinese text reads: The mantra of Guru Karmapa, the Precious King of Dharma, OM MANI PADME HUNG”. The Tibetan text reads: “I prostrate to the Lord of Dharma, Karmapa, OM MANI PADME HUNG.” At that time, he explained, there was no tradition of chanting “Karmapa Khyenno.” Because the Karmapa was considered an emanation of Avalokiteshvara, there was the tradition of reciting OM MANI PADME HUNG, the mantra of Avalokiteshvara. What is more, Karma Pakshi had emphasized the mani practice so much, and when Deshin Shekpa went to China, he also recited it as well, so the six-syllable mantra spread widely in China under the patronage of the Yongle emperor.

There seems to be a profound connection, the Karmapa commented.

The Ming emperors continued to support and spread Tibetan Buddhism after the death of Yongle. For example, at the time of the Ming emperor Xiaozong, there were over a thousand Tibetan monks In Beijing. Likewise, at the time of the Ming emperor Yingzong, they prepared a special place to serve meals to the Tibetan monks and nuns and built a monastery where they could stay. During the Ming emperor Xiaozong, Tibetan monks and nuns were brought into the palace to perform rituals. Míng Wǔzōng, the emperor who invited Mikyö Dorje, showed even more interest in Tibetan Buddhism than his predecessors. He learned Tibetan and used to wear the robes of a Tibetan monk.

When Deshin Shekpa had finished performing the ceremonies at the Linggu temple, he went to Wutai Mountain and spent a long time there. As His Holiness had mentioned the previous day, at Wutai Mountain there is a Xian Tong temple and a stupa of the Buddha Akshobhya, offered by the emperor. This is probably the first Tibetan Buddhist temple built at Wutai Mountain, which is one of four sacred sites in China. In Chinese Buddhism it is the sacred site of Manjushri, and, as such, is the most important site for both Chinese and Tibetan Buddhists.

Though Deshin Shekpa spent only two full years in Chin, he exerted a powerful influence. His students continued to stay in China and took on the responsibility to spread the Dharma. One of the people who invited Deshin Shekpa from Tibet to China, a monk called Zhiguang, became an exceptionally good practitioner and an important translator from Chinese to Tibetan and vice versa. Another great student of Deshin Shekpa was Palden Tashi. He was with Deshin Shekpa in Nanjing, and Deshin Shekpa took him back with him to Tibet and gave him many instructions. Palden Tashi became one of the most famous translators from Chinese into Tibetan in the Ming dynasty. He spent a long time in China, teaching many Chinese people and ministers the Dharma.

Deshin Shekpa’s most famous Chinese lay student was a eunuch called Zhenghe. The emperor Yongle relied on him greatly, and he went to the West seven times. He was among the first ones to cross the ocean to the West and is a really famous Chinese historic figure, who discovered and explored many new places. How do we know that he was a Buddhist? Although many histories say that he was a Muslim, there is a text which was printed in the beginning of the Ming dynasty called “The Sutra of the Lay Vows” that is ascribed to “the eunuch Zhenghe who had great faith in the Buddhist teachings”. He went with armies and great ships to the West, crossing oceans, to work for the emperor. As he sailed across the great oceans, he was protected by the buddhas and arrived safely; thus, he had no obstacles on the path. And because he always had such gratitude and a great heart, he was able to bring back great wealth. He always thought that this was the kindness of the buddhas and because of this he would go to great expense to print many Buddhist texts. For example, he printed ten copies of the words of the Buddha and offered them to well-known monasteries at the various places in China. He met Deshin Shekpa at the Linggu temple. Later, Zhenghe went to Sri Lanka and brought back a tooth of the Buddha and offered it to the Chinese emperor. The Chinese emperor encased it in gold and give it to Deshin Shekpa.

When Deshin Shekpa returned to Tibet, he brought many Chinese artefacts with him, one of which is the great jade seal which is now one of the prized exhibits in the Tibet Museum in Lhasa.

Part 2: Mikyö Dorje’s Invitation to China

The Seventh Karmapa, Chödrak Gyatso, said that in his next life, if there were to be only one Karmapa, he would not bring great benefit to the teachings, and, in one text, he predicted two Karmapas. Accordingly, some people said that the Ming Emperor Zhengde, also known as Míng Wǔzōng (1491–1521), was an emanation of the Karmapa.

Mikyö Dorje spoke about this topic in the autobiography he wrote at Namtö Mountain:

Then the victorious Chödrak Gyatso said,

“To protect the teachings of the Buddha

In this world, emanated bodies

As both the emperor and as the one he revered.

“If the teachings are not protected by power,

The unvirtuous actions of degenerate people will not be tamed.

In the future I will simultaneously emanate bodies

As the sponsor and the object of his worship.

“And thus, sustain the activity,” he said.

Accordingly the Chinese emperor Zhengde said

“I am also an emanation

Of the Karmapa.”

In any case, it is said that Mikyö Dorje’s birth in 1505 and the emperor’s accession to the golden throne occurred on the same day. The emperor had an interest in many different religions, including Islam, and a great interest in Tibetan Buddhism, too. He gave himself the dharma name Dàqìng Fǎwáng, which translates to “Glorious Jewel” and had a stamp of it made. Additionally, there are stories that he wore the robes of a Tibetan Lama, put on a black crown, and said, “I am the Karmapa.”

From the time of Karmapa Deshin Shekpa, there was a tradition of the Karmapas and the Ming emperors sending messengers to each other and making offerings. In particular, during the time of the Eighth Karmapa, Emperor Zhengde said, “In the west, there is a nirmanakaya of Amitabha. He has come for my sake, so he must be invited to China.” On the emperor’s order, a great caravan of ministers, eunuchs, soldiers, monks, and porters, bearing offerings: ritual objects made of gold, silver, and various kinds of jewels; robes; and seats; tea, silks, sandalwood and untold other offerings, in total over 70,000 people were sent to deliver the invitation. [The west here refers to west of China, i.e., Tibet.]

This is mentioned in Mikyö Dorje’s autobiography:

Bring from the west

Amitabha’s emanation to benefit me,

Who is known as the rebirth of the Karmapa,

Back to the great palace.”

His Holiness explained it was important to compare both the Chinese and the Tibetan histories in order to establish what happened, as they sometimes differ.

One history of the early Ming dynasty records that people in the emperor’s quarters told him that a monk in the west knew the three times– past, present and future–and this was probably Dusum Khyenpa. They reported that people from the backward regions said he was a nirmanakya or living buddha. In the Tibetan histories, someone called Domtsa Goshri was the first one to inform the emperor about the Karmapas. He was given the title Goshri by the Seventh Karmapa Chödrak Gyatso and sent to China. At first, he wasn’t believed, and they put him in prison. Later, however, they believed him and released him and questioned him about the Karmapa and they developed some interest. The Chinese histories record that during the time of Yongle, he sent envoys to entreat the Karmapa to come to China, and made extensive gifts and offerings, so many that he actually emptied the treasury. The emperor set the envoys ten years in which to accomplish their mission.

However, the Tibetan histories say that Mikyö Dorje had no choice in the matter. The command from the emperor was so forceful. He thought that if he refused to go, the emperor’s soldiers would abduct him anyway and take him to China, which does suggest, the Karmapa commented, that the figure of 70,000 might be true.

The huge retinue halted and made camp at Rabgang, so as not to offend Tibet. The great encampment sent a welcome party as was customary, but the Chinese minister in charge did not let them enter. Rather than go in person, he sent his officials with an invitation letter to Mikyö Dorje, who did not accept it. He probably sent three or four parties to the encampment, but Mikyö Dorje did not accept the invitation. Finally, in 1520, the minister himself went to deliver the invitation. On the first day, the minister himself saw Mikyö Dorje and offered him a khata and so forth. The next day, the emperor’s invitation itself arrived, and Lord Mikyö Dorje, as was the custom that had been previously written down, went to receive the letter itself and accepted it. The next day, the offerings from the queens, princes, ministers, and most of the other offerings arrived, which were to be later arranged as offerings to the encampment’s shrine. However, when he first met the minister, Mikyö Dorje saw signs that the omens were not good. Then Avalokiteshvara appeared to him in a vision and said that the emperor had passed away so he should not go. So, he declined the invitation to go to China.

Mikyö Dorje was only in his teens at that time, so the Chinese minister had tried to bribe the Karmapa’s steward with gifts. He promised the steward that if Mikyö Dorje were to go to China, the steward would be rewarded with a high rank – guó gōng or duke. The two agreed that if Mikyö Dorje did not go, the offerings not be given to Mikyö Dorje until he agreed to go. Mikyö Dorje was adamant that he would not go because the omens were not good, but in order for the envoys not to get punished by the emperor upon their return, Mikyö Dorje promised that he would go at a later time. The minister did not accept this, took back the offerings, and threatened to destroy Kham. Meanwhile, he plotted with the steward how they could abduct the Karmapa and force him to go to China. Fortunately, the plot was discovered and Mikyö Dorje was whisked away to Central Tibet and safety.

Mikyö Dorje recounts this in his autobiography:

Seventy thousand messengers of the great lord of humans

Came when I was fourteen years old.

They ordered that I go immediately

To be the Chinese emperor’s guru.

At that time, I was not yet an adult,

And even if I were, I did not have in my being

Even a fraction of the qualities

To be the spiritual master of a nirmanakaya emperor.

I was discouraged and despaired of my karma—

What is the fault whereby I had such a title

As being known as the Karmapa?

They supplicated me repeatedly,

Saying I do not have the power

To go above the emperor’s envoy.

They planned to take me, and at that time,

I refused very earnestly.

The retinue of the emperor’s envoy

Became haughty and departed.

So, eventually ,the envoy had no choice but to leave. Yet, it did not turn out well for them. On the way they were attacked by bandits,many soldiers died, and the offerings were lost. As it turned out, not long afterwards, the emperor passed away and there was a new emperor who had no faith in Buddhism, so Mikyo Dorje’s journey would have been pointless. The eunuch envoy was almost executed, but then he was demoted and made a gardener. Many natural disasters occurred in China, and it was said this was because the minister had not given the offerings as the emperor had decreed and because the Karmapa was displeased. The biography reads:

At that time, the emperor, lord of humans,

The propulsion of his life exhausted, passed to a different realm.

At that time, even had I gone,

There would have been no point, other than weariness.

It is not that I had the ability and power

To accomplish the great emperor’s wishes

But did not. Since I lacked the ability

To accomplish them, O emperor,

Whether you are an emanation or not,

If there is any wrong, I confess. Please forgive me.

His Holiness drew some general conclusions from these events.

They show the true character of Mikyö Dorje. Although he faced a lot of criticism for not going to China, not accepting the many offerings and so forth, in fact this is an example of his having no attachment to the eight worldly dharmas. He did what was in his heart and mind. He would not do something because someone made offerings to him or because, as in the case of the Ming emperor, they were important or famous. From the time he was young, he was different and self-determined. He really stood on his own two feet no matter what others said. He used his intelligence to examine a situation, and then act according to his own insight.

When we look at the life stories of great beings, we might sometimes wonder why they did something they did and think that it would have been better for them to have done something else. But, when we look at people, we can only see the external appearance. When we consider the deeds of the gurus, we sometimes fail to understand, questioning what they are doing. However, later we realize that these great masters did the right thing and were examples to us. Sometimes, it may even take a couple of centuries to understand the many situations and know that what they did was good.

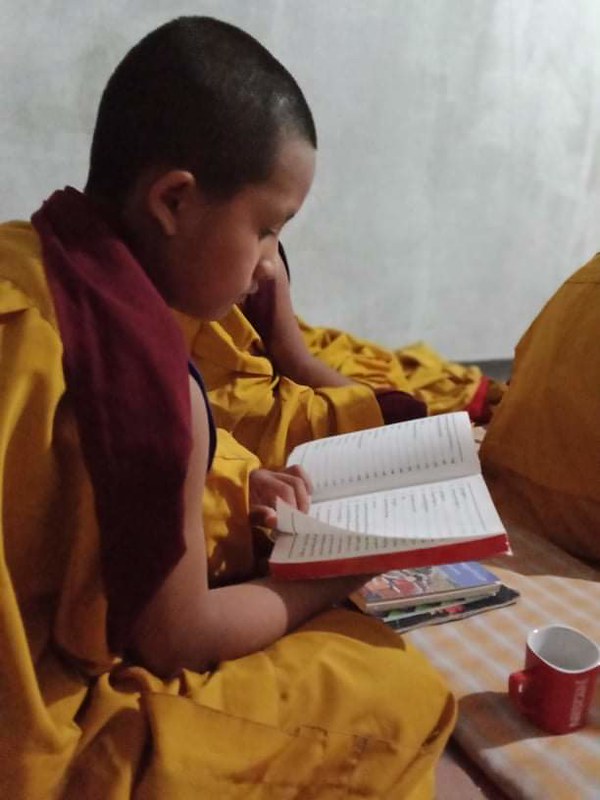

Click the photo to view photo album: