Arya Kshema Spring Dharma Teachings:

Gyalwang Karmapa on The Life of the Eight Karmapa Mikyö Dorje

March 5, 2021

Part 1: Never harming another being

His Holiness continued teaching on Mikyö Dorje’s seventh good deed, as well as introduced the eighth good deed today.

As you may remember from yesterday, it is said that Mikyö Dorje practiced the paths of three types of individuals: the lesser, the middling, and the greater. His seventh good deed discusses his practice of the first path, that of the lesser individual. The text reads:

Once I knew that all suffering that occurs is the result

Of my own wrongs, I could not complete in full

Unvirtuous acts with preparation, deed, and aftermath.

I have not completed an unvirtuous act in this life.

I think of this as one of my good deeds.

For Mikyö Dorje, it was essential to never harm another being as he recognized only suffering would be experienced as a result. According to the Instructions on Training in the Liberation Story of Mikyö Dorje, which explains the meaning of the “Autobiographical Verses of Good Deeds”, beings have been wandering in samsara since beginningless time because they do not know what causes lead to pleasure and what causes lead to suffering. On the other hand, the perfect Buddha told us what we should and should not do. For this reason, in the fifth good deed, Mikyö Dorje spoke about going for refuge to the Three Jewels, the only sources of refuge that can teach the path of giving up misdeeds and practicing virtue.

Although we’ve been taking birth in samsara from beginningless time, our actual nature ultimately is free of birth or arising, staying, and perishing. Unfortunately, we do not know this. As a result, we have many constructions, perceptions, and denials about that nature and our thoughts lead us to wander in samsara.

As we’ve wandered in samsara, we’ve been connected to other beings – as one another’s children, parents, and so forth – innumerable times. We have benefited each other and formed great connections many times before. Therefore, if we harm others rather than benefit them, the fully ripened result will be an experience of terrible suffering. Moreover, the compatible result from harming them will also arise. In other words, not recognizing how other beings have not only harmed but have also helped us throughout beginningless samsara, we inflict harm upon them, and then we experience harm as a result. This is how karma occurs.

Although we have done many things that will cause suffering in the future, if we had thought deeply about their actual nature first, we would never have dared to do such actions. Thus, we must try to guard this thought “I must never dare to do anything to harm another sentient being” throughout our lifetime, never letting it wane. We must also try to prevent thoughts about harming others from arising.

For those of us who say we have entered the Buddhist teachings—studied karma, cause and effect to understand what we should do and what we should abandon—and say we’re applying the antidotes of mindfulness and awareness, we must be cautious when problems arise. Sometimes, when a problem comes up, we blame the place, the time, or another individual, and claim, “I had no choice but to do that”, “I had no control”, and “it was not my fault”. We forget the needs of next and future lifetimes for the sake of having some minor sensory pleasure in this one and we commit unvirtuous actions. Mikyö Dorje did not act in this way. It was said that he would never do anything contradictory to the teachings even if it meant gaining the pleasures and happiness of the gods in this lifetime. His Holiness compared it with there being poison hidden in delicious food and knowing you would die if you ate it. A sane person would not eat this poisoned food, no matter how hungry or thirsty he or she was. Likewise, no matter what difficulties we encounter, it is not right to give up on the true Dharma. Therefore, Mikyö Dorje was very assiduous in giving up misdeeds and accomplishing virtue.

Part 2: Repairing relationships and restoring harmony

Mikyö Dorje was not confident that he was a nirmanakaya buddha as some of his followers believed. He thought that he had been given the title “Karmapa” in this lifetime not because he had the necessary qualities of abandonment and realization but because it was a blessing of all the activities of the previous Karmapas and the buddhas. In this way, he viewed his title more like a name, not as an indication of his attainment. Thus, he said, as long as he remained in this present state of aggregates, of full ripening, stricken by birth, old age, sickness, and death, he would protect himself against karma, cause, and effect.

How did Mikyö Dorje practice what he taught? One way was by reducing conflict and sectarianism between different Tibetan Buddhist lineages. Mikyö Dorje concluded that sectarianism could lead to individuals giving up their liberation, bodhisattva, and tantric vows. For example, monks would go off to battle which in turn would lead to destroying representations of the Three Jewels and the taking of each others’ lives. These kinds of heinous acts would completely destroy the Buddhist teachings and the Sangha community. Therefore, Mikyö Dorje warned followers to stay away from such evil actions and avoid desiring the success of one lineage over another. Although one may think s/he is practicing the Dharma, when one divides individuals into factions and subsequently helps one’s own faction and harms another, s/he is actually acting according to her/his own wishes, desires, hatred, and delusion. Mikyö Dorje pointed out that these were actions of attachment and aversion, not actions of the Dharma.

The Eighth Karmapa understood that attachment to external objects and one’s internal mind, including the attachment to hatred, arrogance and so forth, leads to disharmony, faults, and problems. He therefore decided to leave the eastern region of Tibet, where the Karmapas were popular and powerful,l for Central Tibet, which was ruled by kings who governed by strict laws. Mikyö Dorje’s monks had to follow him as he journeyed to Central Tibet, and they stayed in isolated places as well as in areas where locals had little regard for the Dharma. Mikyö Dorje knew that in such places, he and his monks would receive fewer offerings and less respect. By leaving areas where they had power, sensory pleasures (and therefore attachments, aversion, and disputes) would be fewer. In addition, he created rules to help them live purer livelihoods, where they wouldn’t be able to pretend to adhere to the Vinaya so that they could take offerings. Further, he prohibited meat and alcohol consumption in the Great Encampment.

You may remember from the teaching a few days ago, the Seventh Karmapa established Tupchen monastery in Lhasa and Yangpachen monastery in the north. Some Geluk monks had suspected the Karma Kagyu were trying to deprive them of offerings, and consequently, disharmony between the two lineages arose. Mikyö Dorje attempted to return the monastery to the Lord of Ü, Nedongpa, but Nedongpa rejected the offer. Mikyö Dorje decided to vacate Tupchen monastery – he didn’t even leave one guard there – and allow it to fall into disrepair. Although some Karma Kagyu followers were unhappy that Mikyö Dorje would neglect a monastery founded by the Seventh Karmapa, Mikyö Dorje was trying to restore happiness between the Geluk and the Karma Kagyu lineages.

His Holiness proceeded to recount several examples of conflicts over rank, titles, and heights of seats, which he said was one main reason for disputes and the breaking of vows. Over the years many protocols surrounding the demonstration of rank and respect have been created, including the giving of khatags (silk ceremonial scarves), formalizing who should prostrate to whom, and calculating the height of cushions or thrones (the higher the status, the higher the seat). Disagreements have occurred over rank, protocol, position, and status, over the external ways in which respect is shown. Mikyö Dorje understood that these conflicts harm the Buddhist teachings so he tried to prevent them from happening. For example, when people would come to compete with him, he would treat them well without putting himself in an especially low position nor elevating the other unnecessarily. Mikyö Dorje would also meet with people even if they didn’t prostrate to or prepare a seat for him. Some criticized him for so doing, saying that all of the Karmapa’s greatness, influence, and mystique had been lost, that “he used to have a position as high in the sky as the sun but now, horribly, he has been brought downwards to earth”. In this way, he wanted to prevent disputes and not harm the Buddhist teachings.

Ranks, status, seat heights, and privileges occurred after Tibetan lamas connected with Chinese and Mongol Emperors. These Emperors invited Tibetan lamas to their regions, offered them different coloured seals and stamps, and conferred high titles and positions on them. There had previously been no tradition of rank, position, and privilege such as this in Tibet. In the Vinaya, seniority depends on when a person took precepts – those who took precepts at an earlier point in time had more seniority. In the Vajrayana, seniority is in terms of realization. The monks of Central Tibet’s great monasteries would have to stand outside closed gates waiting to claim their seats. Once the gates opened, they would all rush in and whoever got to the front first got to sit there. Only after the connections with Mongol and Chinese emperors were positions, privileges and ranks given. Before then, there was no question of privilege or rank.

There were many ways that Mikyö Dorje tried to prevent the great stream of misdeeds within himself, but he also tried to sever it within others as well. He instructed both monastics and lay people how to give up non-virtue. As written in the Prajnaparamita sutra:

A great irreversible bodhisattva abandons the ten nonvirtues themselves, gets others to abandon them, declares the excellence of abandoning them, and acts accordingly.

Upon seeing him or hearing Mikyö Dorje teach, many people promised to give up killing, stealing, reneging on their oaths, and being deceitful in their business. Others promised to save the lives of sentient beings and animals, free prisoners, or recite 100,000,000 mani mantras. He would get people to promise not to harm temples or representations of the body, speech, and mind of the Buddha. He had people abide by the fasting vows and asked them to become vegetarian. It was primarily during the Black Crown ceremony that people made these promises. By advising monastics and laypeople alike to give up misdeeds and practice virtue, in the short term he blocked the ways for them to be reborn in the lower realms and opened the gate to higher realms, ultimately bringing them to Buddhahood. This is an example of a great being. If we believe this as true, feeling deeply towards those who brought many to abandon misdeeds and practice virtue, it will bring us much benefit. Trying to be fashionable, trying to get high rank and position, and criticizing great beings are not good; we should avoid these behaviours as much as possible.

Part 3: The Eighth Good Deed – Practicing the path of the middling individual and removing the harmful view of the self

Unless we fully cross the ocean of birth and death,

Nowhere in the three realms are pleasures and riches permanent.

I wondered, when will I liberate forever

All beings throughout space from the three realms of samsara?

I think of this as one of my good deeds.

Mikyö Dorje’s eighth good deed was how he practiced the path of the middling individual. This relates to how having a view of the self and having afflictions in our own being are harmful. In the path of the lesser individual, avoiding harming other sentient beings is the most important. That is the path of karma, cause, and effect. However, not inflicting harm on beings in the short term does not mean they are liberated from harm altogether. This is because in the being’s own continuum, there are karma and the afflictions which are the basis of causing harm. There are also an infinite number of other sentient beings with whom they have a karmic connection, who may harm them.

If we refrain from creating any bad karma, then even if all sentient beings gathered together to harm us, they wouldn’t be able to. If we do not perform the actions that lead to rebirth in samsara, no other being can throw us into it or cast us into lower realms. What harms us ultimately is the view of the self and the afflictions within us. The afflictions generate our motivations and the actual actions we do, the karma, are our misdeeds. There is no greater or more fundamental harm than that.

Up until now, we haven’t seen the view of the self and the afflictions as being our enemy or the cause of harm. We actually think of ego-clinging in particular as being our advisor. These thoughts of cherishing ourselves have resulted in the accumulation of many misdeeds and nonvirtues. Even with the destruction of the Earth at the end of an aeon either by fire or by water, all sentient beings and all possessions will be destroyed, but the continuum of beings cannot be stopped. To stop the sequence of being reborn in samsara, we need to train in the methods and prajna that can free us from karma and the afflictions.

Method is practicing doing what we should do and avoiding doing what we shouldn’t, according to the Four Truths. This includes identifying karma, viewing suffering as being an illness, seeing the Truth of Origin as the cause, knowing the Four Noble Truths and so forth. This is taught in the Three Vehicles and in the sutras and tantras. Practicing them is indispensable. Moreover, we need to have an actual feeling or experience rather than relying on a mere understanding. For example, we should see the afflictions within our being as poisonous snakes. Then we must generate this intention, the diligence, and a strong feeling that we need to get away from them. Mikyö Dorje would tell people that unless we completely eliminate the pernicious illness of the view of the self, the liberation of being freed from the lower realms or achieving samsaric pleasures are not enough.

Mikyö Dorje worried deeply about those without enough food or clothing or those in desperate situations just as though it were happening to himself. Even if they experienced some temporary improvement, he would still worry. He would think “they are freed of their hardship for the time being but does this count as real liberation?” He knew that until they were liberated completely, they would have to experience endless suffering in samsara. However, although he feared the sufferings of samsara for himself and couldn’t bear the thought of the suffering of others, he knew he could help sentient beings. He said the way to free ourselves from suffering is to study and practice what the Buddha taught. The method was practicing the Four Truths and the prajna was realizing the two types of selflessness. He worked hard to habituate himself to this, and he told others to practice the Four Noble Truths in this way.

His Holiness cautioned against practicing the Dharma to gain happiness in this lifetime alone. He noted that if some people don’t have a good house or have many family problems, they say they “lack merit”. They think that practicing the Dharma is to bring happiness and to be free of suffering in this lifetime and they practice with this intention. They go to lamas who tell them there’s no real problem, that everything that arises is the display of dharmakaya. The lamas advise them to rest within confused appearances as they are without being distracted and say everything will work out. “Just sit there”, the lamas tell their students. But many people aren’t satisfied with this response. So they try to listen to, meditate on, and contemplate the Dharma, but they do so to gain happiness in this lifetime. This is pointless. Mikyö Dorje would never do such actions himself, His Holiness stated. We listen to, meditate on, and contemplate the Dharma to attain liberation and the state of buddhahood, not to gain temporary pleasures in this lifetime.

This is a brief description of how Mikyö Dorje practiced the path of the middling individual. The rest of the text is about how he practiced the third path, that of the great individual.

Part 4: Mikyö Dorje on vegetarianism

For the rest of today’s teaching, His Holiness wanted to further explain Mikyö Dorje’s reasons for not eating meat. In large monasteries at that time, many animals would be killed. Similarly, sometimes people wanted to give good food to lamas and their entourage and so a lot of meat would be offered. Mikyö Dorje saw that this caused many difficulties so wherever he went, he would very skillfully get others to give up eating meat.

First, by prohibiting meat consumption, Mikyö Dorje was returning to earlier traditions of previous Karmapas who did not allow meat or alcohol to be brought into the Great Encampment. Second, when Mikyö Dorje was first put on the throne of the Karmapa when he was young, he did not have much freedom or control. All the power was in the hands of the Encampment’s leaders and one of their wives. At that time, all of the animals that were offered to the Encampment were killed and their flesh was eaten.

When Mikyö Dorje was young, people would approach him saying they needed to have Ganachakras with meat and alcohol. Mikyö Dorje felt this didn’t work at all. Those in the Encampment were no longer respecting the Encampment’s earlier traditions, eating meat without any restraint and drinking alcohol. Once Mikyö Dorje gained some control and influence, he made a strict rule prohibiting eating meat and drinking alcohol.

He not only restricted eating meat in the Great Encampment, but he promoted vegetarianism to all Tibetans. In Mikyö Dorje’s commentary on the Vinaya, The Orbit of the Sun, he said even when we do the Gutor, the Mahakala ritual at the end of the year, we should not include meat in those offerings. In the index of his collected works, his advice to Tibetans was that it is inappropriate to eat the meat of defenseless animals.

In the next session, His Holiness would like to teach about the Great Encampment, which is intimately related to Mikyö Dorje’s activities and life story. Once we understand how and why it was first formed, it may provide insight into the Eighth Karmapa’s intentions and actions. Yet, as there is no Great Encampment now, it is difficult for us to form a mental image of what it was, what it was like, and how it flourished. However, teaching on the Great Encampment will be challenging for His Holiness because small bits of information about it are scattered across many different texts. His Holiness then ended today’s teachings with dedication prayers.

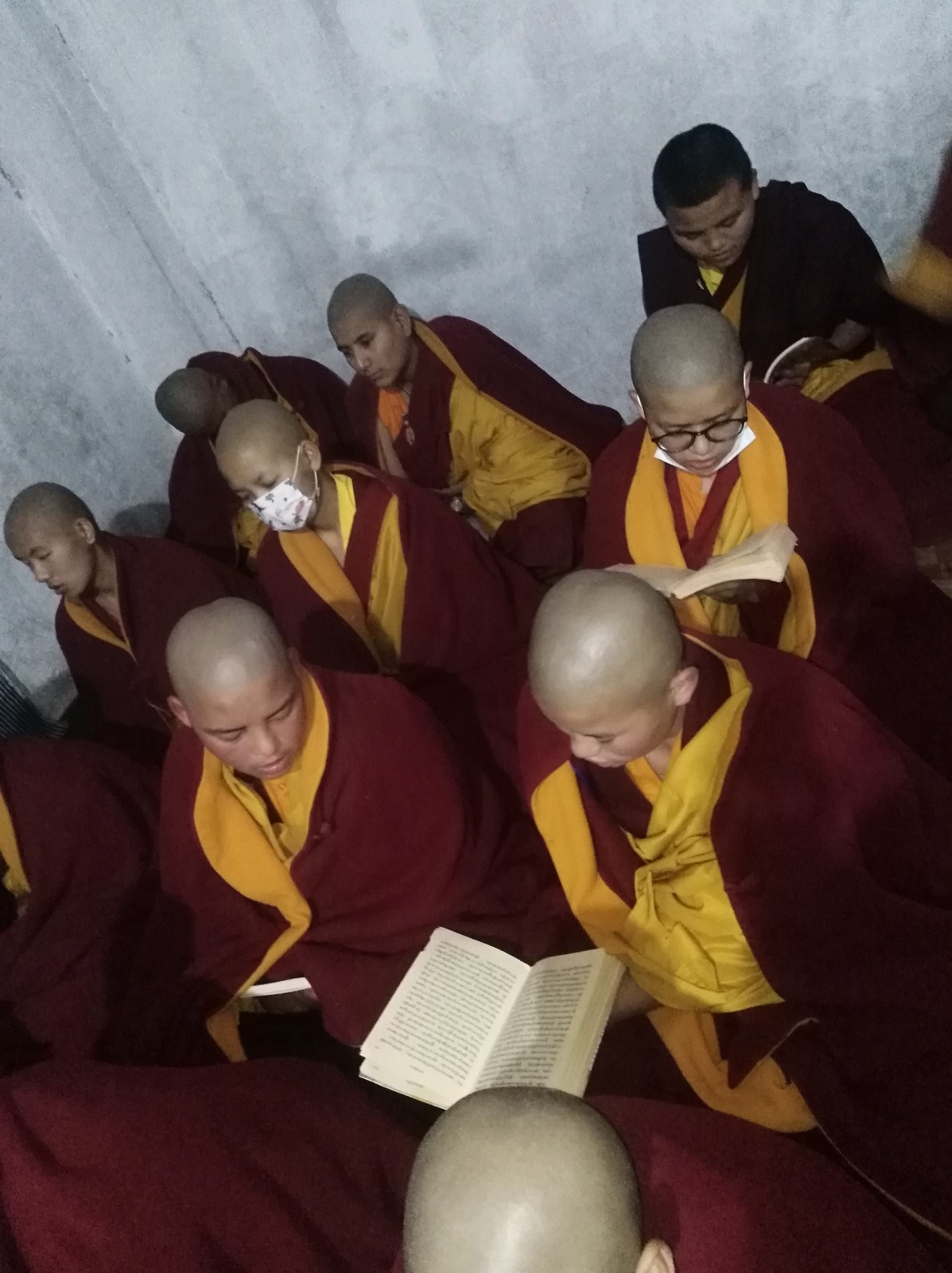

Click the photo to view photo album: