2022 Arya Kshema Spring Dharma Teachings: 17th Gyalwang Karmapa on the 8th Karmapa Mikyö Dorje's Autobiographical Verses

April 11, 2022

On the eleventh day of the Arya Kshema Spring Teachings, the Karmapa said he would speak about the nineteenth good deed from Mikyö Dorje’s Autobiographical Verses “Good Deeds.”

According to the outline from the commentary on Good Deeds by the attendant Sangye Paldrup, there were the two parts regarding the meditation on relative bodhicitta:

a. Exchanging oneself for others in meditation.

b. Taking adversity as the path in post-meditation.

In terms of the second, the Karmapa would continue to discuss the ten sub-topics, explaining the conclusion to the third point to the eighth sub-topic:

8. Taking things going well or badly as the path.

After that he would discuss the ninth: taking hostility as the path.

9. Taking hostility as the path.

The best opportunities for practice are when things are going well or badly

The Karmapa had already spoken about the first two points that were part of the eighth sub-topic: when things are going well or badly, they are the best opportunities to practice. These two were: (a) how to take things going well or badly as the path; and (b) how to take things going well as the path. He would now explain the third point: (c) when things are going badly, how to take bad situations as the path.

Even when we are in the worst time in our lives, we need to think of these times as the best opportunity to gather the accumulation of merit. Water flows downhill and not uphill, and similarly with merit. When you are in a low place or a bad situation, you have more opportunities to gather merit.

The Karmapa then gave analogies:

When you make an investment, later the value will grow exponentially. These days you have bitcoin and other electronic currencies. It used to be cheap but now a single unit of bitcoin is worth tens of thousands of dollars. Likewise, during the worst times of our lives, we experience terrible physical and mental suffering, but through that suffering we can enhance or improve our practice.

Think about the mani mantras we recite when we meditate on Chenrezig during the normal times when we are healthy, and then think about the manis we recite when we have illness and suffering. The manis recited are the same, but the feelings behind them are different. In a crisis, your state of mind is different, your focus brings especially intense prayers and wishes. You supplicate more fervently: your state of mind is not like your ordinary state of mind. The manis are the same, but your state of mind is different. The beneficial power and results are also different and not the same. When we experience suffering, we should not be oppressed by it. If we continue our practice, we can improve, like a bird taking flight.

When we have headaches, stomach aches, and body pains, we cannot focus well, are unable to recite mantras, and unable to recite prayers and aspirations. But if we compare this to the time of death, the terrifying, pitch-black darkness that awaits us, the pain and fear of dying, then we see our present sufferings can hardly be considered suffering. When we encounter suffering or misfortune, or when things do not go as we wish, these situations are like preparations and training for facing the suffering of death.

When we recognize that all hardship and suffering are opportunities to practice and to train our mind, then our practice improves amidst our torments and sufferings. If you can endure hardships, you can move forward. These events are like the hurricanes and tornadoes in our lives that can make our thinking broader, clearer, and more focused in the long term. Only then can we improve ourselves and become wiser. When we think like this, it is good.

One of Jamgön Lodro Thaye Rinpoche’s writings, probably a quotation from Jangchentse Wangpo, says: “The most significant events of our lives are birth and death, and everything else is not important.”

And just as he said, when we experience misfortune, defeats, and highs and lows, the amount of difficulty we have in that situation depends on the level of our own mind, our state of thinking. If you build a stone wall, if an ant sees it and wants to cross it, it will see it as high as a mountain, the same as us climbing a mountain. But a dog will see the wall as something to jump over with a bit of effort.

When there are ups and downs in our lives, some people lose hope, they give up, seeing them as insurmountable hardships. But other people see those hardships like the dog sees the wall. They do not see hardships as great difficulties. They put effort into overcoming the obstacles. These people do not see difficulties as obstacles or as bad, but like a stone staircase that might allow their lives to be better. If you can get on top of the wall, you can look around and see things in perspective. The hardships seem like methods for improving themselves or are the circumstances that allow them to improve themselves. The hardships are an opportunity for us to increase the breadth of our mind and the level of our abilities.

When you use a good knife, it becomes sharper, but left unused, there is the danger it will corrode. Similarly, the previous great beings did not achieve accomplishments because they had some ability that we do not. They did not have some special power. The great beings of the past disregarded hardship. No matter how difficult the hardship, they were able to surpass them, gain victory over the māras, and achieve realization. The greatest difference between us and the great masters of the past is whether we have the courage and confidence. The great masters had the courage and confidence to overcome the difficulties.

When we hear stories of the great masters of the past, heroes like Ling Gesar, they seem to have had great power, courage, and persistence. No matter how many battles they fought, they always won. We think, if only I could be like that.

This shows the difference in their thinking from ours when faced with difficulties and enemies: if there were no difficulties, there would be no persistence; if there were no enemies, there would be no victory in battle. We think of the great beings and heroes as being incredible. They triumphed over hardships, enemies, and māras. They were never discouraged or hung their heads or tried to appease anyone. There were no words like “procrastination” and “depression,” let alone avoidance and appeasement. No matter what hardship or danger occurred, they were able to transform it into achieving results and improving themselves. That is what distinguishes ordinary and great people and is very important to understand.

When you think about the previous incarnations of the Karmapa, some people might think it was impossible that a Karmapa could have misfortune and suffering, but the actual situation was the opposite. Other than in a pure realm like Sukhavati, there is no place in the world where there is no suffering and hardship. Especially in this world, in such a time when the five degenerations are rampant, someone who thinks they might spread the Dharma will have innumerable obstacles from the māras and attackers. A quotation by the Buddha says, “The obstacles are much more plentiful than the Dharma that is so rare.” The attackers and obstacles are like rain, so you must face up to many hundreds of dangers and sufferings. It is like being in a battlefield surrounded by thousands of enemy soldiers. There is no escape; you need to do what you can to get out, even if it means taking a path that sheds blood to escape. You are surrounded by the māras and the obstacles. That is the reason bodhisattvas are called heroes, the word sattva can be understood to mean a hero or warrior. If there were no hardships or obstacles, there would be no need for courage, there would be no reason for bodhisattvas to have heroic minds.

Likewise, the hardships that each of the Karmapas encountered were different in degree and form and in the way they appeared. In the future, if I have an opportunity, I would like to speak about that.

During their entire lifetimes, the Karmapas endured hardship and loss, but they have left us a treasury filled with light and jewels, taking the suffering onto themselves. There is a saying in the world, “The greater your skills, the greater your responsibility. The greater the responsibility, the greater the pressure.” The various incarnations of the Karmapa knew how much pressure they were under, and how great a responsibility they bore.

Since we do not carry the same responsibility, we do not know the difficulties they had and the pressure they were under. What we can know is that they had such great responsibility and were under great pressure, yet they were never afraid or discouraged, never tried to avoid hardship. They transformed all the hardships and difficulties into conditions to improve themselves and grow, and with great courage they faced these hardships, gathered the accumulations, and brought benefit to others.

It is important for us to learn from them. There is no point in complaining about our suffering. For most of our lives, things will not go as we want, because the nature of life is suffering. In the future when something goes wrong, we should immediately think, “I have had this difficulty, the difficulty did happen, if there was some way to prevent it but it did happen, so I just got an opportunity to practice and accumulate merit.” In the very least, even if we face great dangers every day of our life, we can use them as conditions for improving and advancing ourselves. The degree to which we can face hardship and keep moving forward and not give up no matter how much loss we have in life, this is the amount that will make us grow stronger and more courageous. As a result, we will not get discouraged or lazy, much less give up. We need to see how we can transform difficulties and hardships into circumstances as aids to the Dharma and to improve ourselves. Here the Karmapa concluded the discussion of the third point.

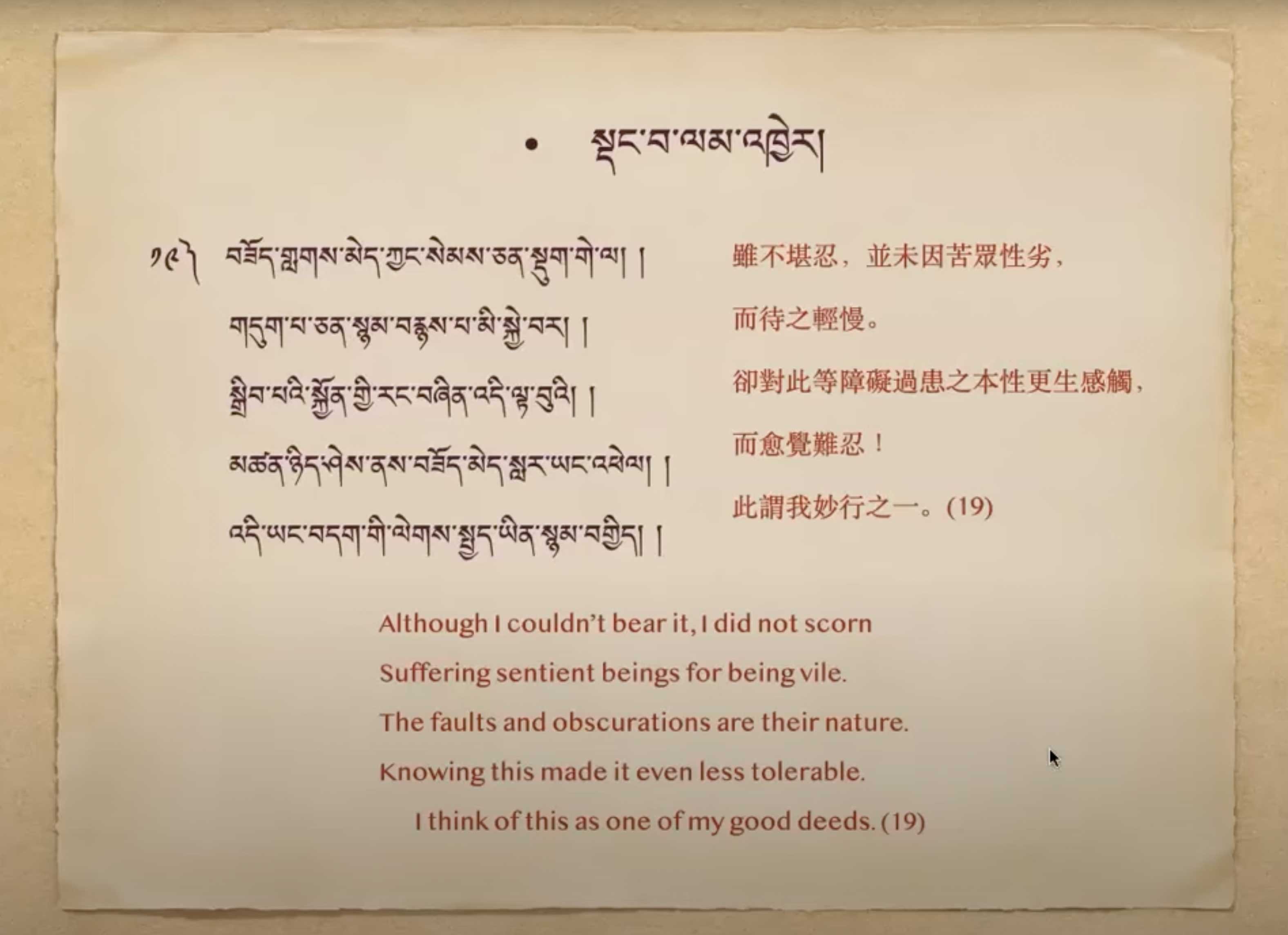

The Nineteenth Good Deed: Taking hostility as the path (v. 19)

Although I couldn’t bear it, I did not scorn

Suffering sentient beings for being vile.

The faults and obscurations are their nature.

Knowing this made it even less tolerable.

I think of this as one of my good deeds. (19)

There is a saying in the Fine Explanations of the Sakya by Sakya Pandita Kunga Gyaltsen:

Exalted beings are brought more harm

By their retinues than their enemies.

Aside from the parasites in its body,

What other beast could eat a lion?

The main point here is that when you talk about a great being, a great person, or a great lama, more of the harm comes not from their enemies, but from their retinues, their students, and their attendants. The people who harm them the most are those who serve them. The line, “Aside from the parasites in its body,” means no other living being would dare harm a lion, but all the parasites living on its body can harm the lion. This is what it is like. It also says in the sūtras of the Buddha:

The Buddhadharma cannot be harmed

by any outside people or any outside religions,

but who can harm the Buddha’s teachings?

They are the people who say they uphold

the Buddha’s teachings and that they are Buddhist,

these are the people who can harm the Buddha’s teachings.

For that reason, when you think, how will the Buddha’s teachings be destroyed? The Buddha prophesied, “In the future, my teachings will be destroyed when the people who uphold the teachings, the people who say they are Buddhists, the monks and nuns argue and dispute each other and say, ‘I’m in accord with the Dharma and they’re not.’ They will always be disputing each other, and disagreements cause a schism and will destroy the teachings.” The main point is that the teachings of the Buddha Śākyamuni are weakened by internal disputes. The teachings of Buddha Kaśyapa were destroyed by the laziness of the bhikṣus and brought the teachings of Kaśyapa to disappear. The greatest harm came not from outside but from the inside, from the students who said they held the Buddha’s teachings.

When thinking about Karmapa Mikyö Dorje, he treated people with unbounded kindness and love, but many people did not appreciate his kindness and began to harm him. Not only did Mikyö Dorje not respond to harm by causing harm, but he continued to treat them with great love. He cared for these people greatly both with dharma and materially, but in the end, they would say, “He wasn’t kind to us at all.” They would not say anything good about him. But for ordinary people that was understandable.

But some people, geshes or scholars, would come to Mikyö Dorje giving material gifts without reserve. In terms of the Dharma, he fulfilled all the wishes they had, but later he taught something that didn’t quite satisfy their hopes and wishes, so they would criticize, scold, and abuse him, thinking, “The Karmapa did not treat me compassionately, he didn’t think I was important, so I’m going back to my homeland to do a scholar’s work, one day I’ll become a well-known scholar, he’ll see.” Not only did they not repay his kindness, but they behaved badly and thought of him as even worse.

But Mikyö Dorje did not get angry. He did not have the slightest wavering or change in the way he thought about them, he was still relaxed, spoke in a carefree way, and looked upon them kindly. He still gave them whatever things were appropriate. By acting in this way, he was able to tame the mind streams of those who had a bit of merit, and they became more receptive to the Dharma. For some people though, no matter how much he tried—he saw that nothing he did would be of any benefit—still, even for those with no fortune and no merit, he never gave up on them, protecting them compassionately. He always prayed for them; he still brought them benefit. He never gave up on them.

The Karmapa announced the break and after reconvening he continued:

Karmapa Mikyö Dorje always responded to harm by bringing benefit, he saw enemies as friends, and never had bias toward another school. He was never stingy and always he gave away things without reserve. He never had attachment to friends or aversion to enemies. He never kept things, giving them away without any reserve, and was never attached or averse to help or harm. Some people said he was mercurial—that he was without stability, easily swayed, and gullible—that he had a limited way of thinking, no matter what he did, he was always too extreme, he did not know how to practice for the proper occasion or time. They would say, yes, he was a lama but, in worldly terms, he was shunned in society. But even with the people who disparaged him this way, Mikyö Dorje never blamed them and never looked open them badly. He said, it was one way of looking at him. The reason why Mikyö Dorje was never ruffled with others’ bad behavior was probably because he did not have such high hopes for ordinary individuals, so he never felt really offended by them. How do we know this? His attendant, Sangye Paldrup, witnessed this himself.

Sometimes when students came to see Mikyö Dorje, they were not able to say things the way they wanted to, fearing they would offend him or cause him to worry. Mikyö Dorje always said to those people, “There’s no need to worry about me getting embarrassed. I don’t get embarrassed. I don’t get upset. I don’t feel problems about it. These are ordinary individuals, so they cannot transcend that nature of being ordinary individuals. It is as said in the Way of the Bodhisattva, ‘Unruly beings are as vast as the sky’.”

He understood why sentient were untamed, uncouth, and bad people, so Mikyö Dorje never could see sentient beings badly. In the Maitreya Aspiration, Maitreya said, “The Buddha never vilifies beings whose minds are stained.”

When buddhas and bodhisattvas saw beings do terrible things, obscured and controlled by their karma and obscurations, even when these beings did terrible things, the buddhas and bodhisattvas never got embarrassed or thought these beings were bad. Mikyö Dorje felt the same way. Until people could abandon their natures and continued to harm him, or repaid his kindness inappropriately, he did not feel particularly upset. Sangye Paldrup heard him say this.

Then the Karmapa returned to summarizing the main point of the nineteenth stanza:

Taking Hostility as the Path: When people harm you or have a grudge or resent you, how should we see them and what methods should we use?

This main point contains the following:

1. Think about it in terms of the eight worldly concerns:

(a) There are people who harm and threaten us. When we think about them, even if we had no connection to them before, or they are people whom we have treated kindly but then they harm us pointlessly, or intentionally harm us, at that point what should we do?

(b) When other people insult and criticize us, what should we do?

The Karmapa explained (a):

When someone intentionally tries to harm us, the way we need to think is that we can probably guess what type of karmic ripening they will experience in the future. If we think in terms of karmic cause and effect, if they return our kindness with harm, they will experience a bad result. If we have that understanding—they will experience an unbearable and terrible result because they are controlled by their strong afflictions—when they fall into that state, we should feel great compassion.

From another angle, when someone causes us harm, most people get angry or have mental suffering. Most people think, they insulted me, blamed me, mentally injured me, so we get angry and get upset. But how is it that we are harmed, how are we injured?

There are basically four types of injuries. (1) Losing something or someone we treasure; (2) Someone lists our faults and criticizes us; (3) Causing physical or mental pain or discomfort; and (4) Giving scorn and insult.

When we look at the eight worldly concerns, these four injuries fit in exactly. There are the four positive dharmas and the four negative dharmas. The injuries are basically the same as the four negative dharmas and can be included in these four concerns.

These concerns ultimately come down to our own attachment. If we do not get delighted or upset about things, it immediately affects our mind.

Taking the first of the four dharmas: losing or not getting what you want in terms of something or someone; and second one: losing what you already possess—these bring mental suffering and consist of two different parts.

In terms of losing or not getting things, or being separated from someone you love, we have mental suffering. What do you do during these times?

If we lose our wallet and money or possessions or suffer a financial loss, consider this as the practice of generosity. If you can think in that way, it is good. This is because generosity is when we give someone something we would not ordinarily be able to give, something that is precious to us and that we are reluctant to give. We should think, “If I don’t have this, I will miss it, but this poor person has nothing so I will give it away.”

Giving someone something we do not need or have no use for is like getting rid of old things—it cannot really be called generosity. We should give others whatever things we treasure and cherish. If we give up something we will miss, that is the practice of generosity. As said in the Way of the Bodhisattva, “Generosity is the wish to give.” Generosity is the antidote to stinginess. Also, if we are able, we should not think about the person who took it, we should have a benevolent attitude—may they receive some benefit and may they never have any bad result—that is extremely beneficial. That is the practice of the bodhisattvas.

Your initial thought that you have lost something dissolves, and it becomes the thought that you have made a gift. This becomes a cause for gathering merit. It is like the saying: the stone that kills two birds, one method accomplishes two great purposes.

Second, if there are people you love or who are close to you, and they harm you by leaving or betraying you, how should you think? We have to think about this carefully.

The Karmapa said to consider this in terms of yourself. If the person you love has discovered that you left or betrayed them, the person who really believes in you would still believe in you, even when the situation occurred. No matter how much someone else would try to split you from your beloved or slander you, the person who loves you would still believe in you and would not leave you. It is like a loving mother: there are only a few people who will be behind you in your life. Many people might say they are your friends, but if you are in a bad situation, only a few people will back you up. When you are in difficult situations, only a few people will believe in you.

We can look at the stories of the great beings, who were slandered or set up for people to suspect them. Devadatta made false accusations and even tried to kill the Buddha Bhagavān. Also, many non-Buddhists became jealous, slandering and creating suspicions to make others doubt the Buddha, even trying to kill the Buddha. But great beings do not get unhappy, have resentment, or think of revenge against those who have betrayed them. In place of that, they meditate on sympathy and compassion for the person wanting to cause harm.

For example, a loving mother whose child becomes a teenager. The child stops listening to the parents, then stops coming home. The mother still loves her child regardless of what the child does. She does not feel distanced from her child but rather feels more responsibility for them. There is no reason to feel upset or grieve over someone who has abandoned us. That person will gradually change over time, and one day that person may possibly understand and think about what happened.

First, as a dharma practitioner, it is not correct to expect those we treat well to return that respect. If you have been treating someone well thinking there will be a beneficial outcome, when it does not happen, it will cause a lot of pain.

Second, bodhisattvas need to work for the sake of sentient beings. They need to benefit sentient beings: both good and bad. They have to work for the sake of bad people too. It would be unrealistic to expect a good return from someone of bad character. If you did, you might feel discouraged when they treated you badly.

There is a story from the Mahāyana—not the foundation vehicle—where during one lifetime Śāriputra did rouse bodhicitta to achieve buddhahood. He made the resolve to bring all sentient beings to buddhahood and practiced in tis way. But one day a māra came and thought, “I need to make an obstacle and change into a brahman to cause a problem.”

Then the māra said, “Please give me your hand.”

Śāriputra immediately cut off his right hand and gave the hand with his left hand.

When he did this, the māra said, “You just gave this to me with your left hand! This is disrespectful!” It was considered disrespectful because in India, the left hand is used for cleaning when going to the toilet.

It was at that point that Śāriputra said, “If it's this difficult to benefit a single sentient being, there is no way I can benefit all sentient beings!” This was how Śāriputra gave up on sentient beings and lost his bodhicitta.

This is the general idea of this story. When a bodhisattva is working for all sentient beings, the biggest obstacle is expecting something in return. Expectation becomes an obstacle to enlightenment. From the perspective of a dharma practitioner, especially one practicing bodhicitta, you need to accept all sentient beings with loving kindness and compassion, and treat them all with equanimity. You must understand that includes not only the ones who treat you well, but also the ones who oppose and harm you.

Think about and understand what causes beings to behave the way they do, and do not have calculating thoughts about them. Treasure and love them, just as a loving mother will care for her children with love. That shows we have loving kindness and compassion. If we do not, if something does not quite match our wishes, does the person become a hostile enemy? Is that how it is? When something does not happen as you like and you get upset, if someone does not do what you want, do you treat them as an enemy? That is the loving kindness that is attached to your own selfish interest, only to your own needs. It is not the loving kindness of only thinking of other sentient beings’ needs.

Then the Karmapa discussed: (b) when other people insult and criticize us, what should we do?

In the Eight Verses for Training the Mind by Geshe Langri Thangpa, the great Kadampa master said:

When others out of jealousy, scold, insult,

and treat me in other unreasonable ways,

may I take such defeat upon myself

and offer the victory to others.

When someone else, out of jealousy, criticizes, scolds, or insults you, and does other inappropriate wrongs, you take the defeat upon yourself and give the victory and benefit to others. When other people are verbally insulting and criticizing us, what we need to think is: the person who insults us has the fires of hatred and winds of jealousy blowing in their minds, because they have less merit or such strong afflictions or because they say various harmful things verbally.

If we think carefully, it is because they do not have any control over themselves; the afflictions are stronger than they are. They are controlled by the afflictions. It is like someone who beats us with a stick. We don’t get angry at the stick —someone uses it to beat us, but the stick doesn’t beat us on its own. When others disparage, criticize, or insult us, from one angle, it happens because of a fault of our own, the other person turns up the volume and makes it big. Ultimately, it is our attachment that makes the fault become very big.

We need to use that opportunity to turn our attention inward and examine ourselves well. Ordinarily people cannot see clearly what their own thoughts are. Although you see others with your eyes, you can only see yourself with a mirror. We have two eyes to see other people but to see our own face, we don’t have eyes to see our own face, we need a mirror. Such is the case with our own faults. Otherwise, we only see other people’s faults. We are always looking outward, and because of that, it seems that all the mistakes are made by other people, and we don’t see our own mistakes.

The great beings think the opposite of that. They say, “All the faults are my own, all the qualities are someone else’s.” Geshe Langri Thangpa said, “No matter how many texts I read, I only see one point, and that point is, ‘All the faults are mine, and all the qualities are sentient beings. No matter what book, I don’t see any other critical point but that.”

The old Kagyu forefathers said, “Whether we know how to take up good deeds and give up bad deeds in karmic cause and effect, it comes from seeing your own qualities and others’ qualities. Only when we can see our own faults will we able to properly do what we should do. If you are not able to see that, when you are mistaken you can’t give something up, this is an important point to understand.

When others criticize us, we should think that it is through others’ kindness that I am able to see my faults. I can find a way to correct and improve myself. If we think we are completely innocent when we have received accusations—at this point, we may think we have done nothing—but in the past lifetime, we did something wrong. By looking at karmic cause and effect, when we think we are getting wrong accusations, we should think of the accusations as karma from the past lives.

When other people criticize us, we should know fix these faults and not to let them happen. We should be peaceful, measured, relaxed, and examine ourselves well. If we can correct ourselves, we can become a new person.

At this point the Karmapa said he would tell a story. He had not been able to discuss every the four dharmas, he had only been able to describe two, but said he would talk about the remaining two the following day.

He began to tell a story of Milarepa:

In Tibet, everyone recognized Milarepa as an example of a Dharma practitioner. All dharma legends accept this. But even for a practitioner like Milarepa, people tried to harm him. When he passed away, he was given poison and died. But who gave it to him?

There are different explanations. As taught in the Liberation Story of Milarepa by Tsangnyon Heruka, he said that there was a Kadampa Geshe Tsagpuwa who poisoned him.

The oldest stories were by Milarepa’s closest eight disciples.

In the liberation story by Karmapa Rangjung Dorje, in his Black Treasury, it said that Geshe Tsagpuwa was not the poisoner.

In the area of Nyanga and Ting, there was a bönpo, or shaman, named Tingtön Jangbar. His income depended on his work as a shaman, giving treatments to the locals for illness and warding off famines. When Milarepa stayed in that region, the blessings of Milarepa resulted in very few famines and epidemics. The bönpo then lost his income, no one invited him to come, and he had nothing to do. Milarepa was the cause, so the bönpo tried to murder Milarepa by offering him poison. Although he tried repeatedly, Milarepa would not accept the poison.

One day Tingtön Jangbar met a leper woman. She had a very difficult life, so he said he would give her a turquoise if she would offer yogurt to Milarepa. At that time in Tibet, turquoise was very valuable as Tibetans traded turquoise for gold when they went to India, so she agreed.

The bönpo said, “I will give you this turquoise, but beforehand you must give this yogurt to Milarepa.” Without her knowing this, the shaman put poison into the yogurt. The woman took the yogurt and went to Milarepa. Milarepa looked at her, opened his eyes wide, and said, “Oh… I will eat this so you can get the turquoise.” and he ate the yogurt.

After eating it, he said, “Poor thing, you are in such a terrible state. I am a yogi who has abandoned ego-clinging, so you will have no misdeed or ripening. But it is not right for you to use this cup.” He washed the bowl before giving it back to her.

Milarepa got very sick and all his students, the repas, wept. But Milarepa looked in the sky and sang a song. The main point of the song was, “May all illness, spirits, misdeeds and obscurations be like jewelry for a yogi, may they be more valuable for us, and may they be the situation for us to improve.” He prayed for the bönpo to be freed from his evil intentions and the woman to be freed from all her problems. None of the repas knew he had been poisoned. They did not know the bönpo had poisoned him and Milarepa did not tell them.

That night, the bönpo was punished by the dakinis and died. To purify the bönpo’s misdeeds, Milarepa sang a song:

The poor bönpo! He died before me. He thought I would kill him, but he died first, a very bad situation. May all my virtue and happiness and the virtue in the three times purify the bönpo’s misdeeds. May I take on all his suffering and purify him of it. In all times and all situations, may he meet virtuous friends, and may he always be parted from negative friends, may he always meet virtuous beings. May he rouse bodhichitta for all beings.

Then one of his students, Drigom Repa, asked Milarepa why he had made the prayer for the bönpo. Milarepa replied, “That bönpo killed a lama in the past and so is going to hell. He also poisoned me.”

Whether this was about the killing of a lama in the past or Milarepa himself, Drigom Rinpoche asked, “If you knew he was giving poison, why did you take it?”

Milarepa said, “I took it and prayed, thinking maybe it would liberate him.”

Drigom Rinpoche asked, “Is it possible it would liberate him?”

Milarepa said, “It probably is.”

From Milarepa’s own perspective, whether he had been poisoned or not, when it came to the time of passing away, it made no difference, so he drank the poison knowingly.

The Karmapa concluded:

When I think about this, even when other people have an evil intention towards you and harm you, Milarepa would do whatever he could to help, not only to bring temporary benefit but the ultimate benefit. This is the kind of great good deed that Milarepa did. These are things we all need to study and learn for ourselves. So that is enough for today. Now we will have the dedication prayers.

Dedication prayers were made.