Arya Kshema Spring Dharma Teachings: 17th Gyalwang Karmapa on the 8th Karmapa Mikyö Dorje’s Autobiographical Verses

April 1, 2022

Previously, the Gyalwang Karmapa had explained how Mikyo Dorje was falsely accused of writing a letter refuting Nyingma Tantra as not real Buddhadharma. He now continued his analysis of the controversy in the context of the thirteenth good deed from the Autobiographical Verses “Good Deeds”:

To bring benefit and happiness to everyone throughout space,

I spoke kind words distinguishing what to do and what to reject.

How could I ever, in any situation, say harsh words

That would make myself and others circle in confusion?

I think of this as one of my good deeds.

His Holiness clarified he would be focusing on dharma history in order for everyone to fully understand the situation and the main points clearly.

An historical overview of Nyingma Tantra

In the Tibetan Vajrayana tradition, there are two transmissions of the teachings —the Earlier or Ancient and the Later or New transmission [respectively Nyingma and Sarma]. During the Later transmission, the Dharma kings Yeshe Öd Jangchup Öd, and Podrang Shiwa Ö, the great translator Lochen Rinchen Sangpo, Gö Khukpa Lhetse and others wrote refutations of false mantras. This referred to the practice of secret mantra but specifically to situations where there were inappropriate usages of mantra. At that time, there was no clear distinction between the ancient and new tantra as there is now, and the main object of the refutation was those who engaged in false secret mantras of union, liberation, and so forth. They were not refuting secret mantra but rather refuting wrong uses of secret mantra in ancient [Nyingma] and New [Sarma] traditions. They were not objections to the Nyingma tradition.

When Atisha came from India to Tibet [c.1042 CE], he visited Samye, the largest monastery in Tibet at that time. In the library there, he discovered many Sanskrit manuscripts of secret mantra dharma texts which he had never seen in India, even though he was the abbot of Vikramashila. He was amazed to find them in such a remote place and expressed delight at the achievement of the Tibetan Dharma kings, praising them highly and calling them bodhisattvas. This is evidence that a collection of secret mantra manuscripts existed in Pekar Kordzoling, the library at Samye.

Later, Tropu Lotsawa Jampa Pel [c.1172-1236 CE] found a Sanskrit manuscript of the Guhyagarbha Tantra, also in the library at Samye. This tantra is a most important Nyingma source text, so he sent it to Chomden Rikral, a renowned scholar who was very important in the compilation of the Kangyur and Tengyur. Having read it, Chomden Rikral accepted its authenticity and acknowledged that the Nyingma had an authoritative source. He wrote a text, the Guhyagarbha: A Practice Ornamented with Flowers. Further proof of its authenticity is found in the great Sanskrit commentary on the Buddhajñāna tradition of Guhyasamaja by Viśvamitra. This cites many quotations from the Guhyagarbha, proving that the Guhyagarbha Tantra existed in India before it came to Tibet.

His Holiness commented that some had pointed out four faults in this tantra:

i) It uses the phrase ‘thus have I taught’ not the more usual ‘thus have I heard’.

ii) The explanation that the ground is immeasurable is illogical.

iii) It says there are four times instead of three, which is also illogical.

iv) The principal deity of the mandala is Vajrasattva, which is inappropriate.

However, the Karmapa observed that the Sarma tantras also have similar explanations, so having these four faults does not prove that it is not authoritative. He gave further evidence in support of the authenticity of the Nyingma tantras. The Eight Classes of Illusion, and the commentaries on Guhyagarbha by Nyi Öd Sengge and Buddhagupta are listed in the Pantangma catalogue, one of the oldest Tibetan catalogues of sacred texts. This shows that many of the Nyingma texts were present during the early spread of the teachings to Tibet. Pandita Smritijñāna and Lotsawa Rinchen Sangpo both translated Sanskrit works into Tibetan, as testified by Chomden Rikral, who had a vast and broad knowledge of the Kangyur and Tengyur.

Similarly, the Sakya Pandita said that there was a root tantra of Vajrakilaya translated from Sanskrit, and Tarlo Nyima Gyaltsen also said he saw a Sanskrit manuscript of Vajrakilaya in Nepal. Therefore, it is possible to say that practices found in the Nyingma tradition were also present in ancient India. Hundreds of ancient Tibetan manuscripts were found hidden in the caves at Dunhuang. These manuscripts include an account of the origins of the Vajrakilaya tantra and a small collection of Dzogchen texts by Buddhagupta.Therefore, His Holiness concluded, it is not appropriate to dismiss the Nyingma tantras as false without thoroughly examining and researching the evidence.

The Dzogchen teachings on mind, space, and instructions were probably not widely known in India, but, as tantric practice in ancient India was taught in strict secrecy, that is not proof that they were completely non-existent in India or inauthentic.

Vikramashila was the centre of Vajrayana tantras in ancient India and Atisha was the abbot. He had also been given the keys to other monasteries, so his knowledge of tantra was broad. However, when he was at Samye and saw so many Sanskrit Vajrayana texts that were not extant in India, he said it was miraculous, and that he had lost his pride in being learned in secret mantra. We need to reflect on this. From this account, we can deduce that at Samye at that time, there were many tantras and secret mantra texts as well as tantras on Dzogchen that were not extant in India.

Some later scholars argue the Nyingma tantras are incorrect because the explanations in the Nyingma tantras differ slightly from those of the Sarma, but based on that alone, it would be difficult to maintain that they are not valid. For example, the explanations in the tantra differ from those in the Prajnaparamita sutras, but we do not say they are invalid because of that. If we make objections without considering the issue from all angles, there is a danger that we will end up slapping ourselves in the face.

Primarily, whether a dharma lineage is valid and whether its sources are reliable depends greatly on whether there is a clear, logical history of its origins. Generally, ancient Indians saw little point in making a written record of what they had seen with their own eyes. They took little interest in history. Consequently, it is difficult to even determine when the Buddha was born and died. Even those dates are disputed, and the lack of a written record even raises a further doubt about whether the Buddha actually existed.

In comparison, Tibet was a little better, but historical documents from the time of the Ancient transmission are scarce. There was a period of time when Tibet became fragmented, and the history is a blank. This creates great difficulties for researchers into the history of the Nyingma Ancient Translation school. The Karmapa gave Guru Rinpoche as an example.

The only namthar of Guru Rinpoche which takes the perceptions of ordinary people as a basis is the one written by Taranātha. The others are mostly terma [revelations], and they contain differences in their accounts. Guru Rinpoche is said to have gone not only to Ütsang (Central Tibet) but to Bhutan, Amdo, Kham, and everywhere in Tibet, even the most minor place: “There is no place he didn’t set foot…” Even regarding how long he spent in Tibet, many things are difficult to fit with the dates of dynasties and so forth.

For that reason, we need to distinguish between common and uncommon namthar, compare dates with the reigns of kings, and use modern research techniques. His Holiness said he viewed it as an essential thing to do.

Many Tibetans have misunderstandings about the difference between the views of Zen and Dzogchen and the development of the Dzogchen view. In this context, the Lamp for Dhyana by Nup Sangye Yeshe is a crucial text. It contains invaluable material on the Chinese Huashang or Zen tradition and also contains a lot of material on the Dzogchen practice. Nup Sangye Yeshe’s dates still have to be determined, but the Karmapa suggested the most logical was that he was a contemporary of King Ngadak Palkhor Tsen.

Historically, there were many objections to the Nyingma dharma. Some were in order to rectify corruption in the texts, some led to an understanding of a particular philosophy and practice, and others were to clarify history and events. So from one angle, they had a positive influence. Thus, instead of reacting to these objections to the Nyingma as something to be discarded or as inauspicious, the Karmapa thought it was more beneficial to take them as the basis for study and research.

Karmapa Mikyö Dorje and the Letter of Objections to the Nyingma

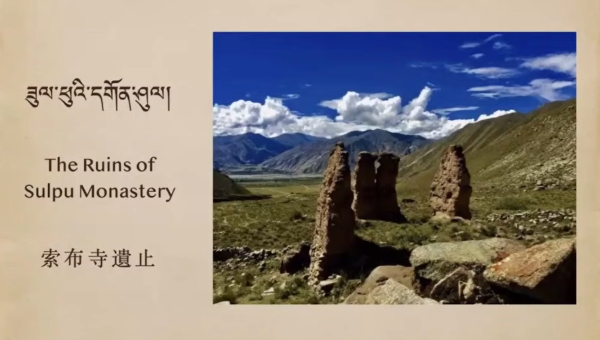

The Karmapa began by showing the front cover of a book containing thoughts on the objections to the Nyingma, which was published as part of the “Karmapa 900” commemoration.

Karmapa Mikyö Dorje wrote many works, including commentaries on sutra and tantra. This shows that he had a great interest in Buddhist philosophy and practice and that he had his own particular viewpoint. Because of this, he was not someone who was fooled into thinking that there was a slim book called “the gurus pith instructions.” Instead, he was someone who worked hard to study all the great texts in the Kangyur and Tengyur and was very familiar with the entire Buddhist corpus.

Because scholars and researchers hold different philosophies and religious traditions, there are often differences in thought and perspective. Raising doubts and objections, making corrections and adjustments, and engaging in discussion are the methods used by everyone who engages in the study of philosophy. This is how scholars work, not just in Buddhism, in both East and West. For someone such as Mikyö Dorje, who was a scholar and the author of many commentaries, it goes without saying that he would raise doubts and objections for discussion.

When discussing whether or not Mikyö Dorje wrote the letter objecting to the Nyingma, before determining anything, it is essential to consider the background situation and reasons. Just looking at the colophon which states he’s the author is not sufficient.

Although the Karmapa had already examined this issue previously in the teaching, he said that it was necessary to look at it from many different angles.

The letter of objections appeared when Mikyö Dorje was about forty-six years old, and he wrote his response shortly after. In the response, he denied writing the letter and responded to its questions. However, some people did not accept his denial. As the saying goes, “Words follow the wish to speak,” so we need to consider the author’s character before we decide whether he would have written it or not.

His Holiness said that he had a degree of familiarity with Karmapa Mikyö Dorje’s work and saw him as someone who habitually raised questions about the philosophy of the Sakya, Geluk, Kagyu, and Nyingma and always engaged in a lot of dialectical debate. He clearly writes about his own views and thoughts concerning other traditions in his various works, without concealing or holding anything back. In particular, regarding the Nyingma, he wrote in his Words Distinguishing Dharma from Non-dharma that the view taught in Dzogchen and the division of the philosophical schools was not generally accepted among Buddhists; that methods of manifesting luminosity by squeezing the two eyes and so forth were not valid; and that other than the terma Atisha extracted from a pillar in the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa, the termas revealed in Tibet were not authoritative.

Similarly, in the Dialog with Gyatön Jadralwa, which was a response to the statement that Guru Rinpoche was superior to the Buddha in five ways, so there could be no faults in the lineage of his disciples. Mikyö Dorje argued that the scriptures which said this about Guru Rinpoche were speaking figuratively and not definitively. That alone is not evidence that he disliked other schools and, in particular, the Nyingma. He was expressing his own opinion on various different philosophies and schools. He was not claiming this to be an absolute, as we can tell from his other works.

The Karmapa now put forward the arguments against Mikyö Dorje being the author of the letter.

It was Mikyö Dorje’s character to be very direct and blunt. He was unable to hide whatever he thought; he probably couldn’t help himself, and spoke out directly. He accepted that he said whatever came to mind, and his student, Pawo Tsuglak Trengwa, confirmed this. It was his character. Also, he was a very logical thinker who could easily spot a fault and then would speak out. In this context, it is true that he did raise objections to the Kagyu and other schools. We cannot deny that. But to use those objections as a basis for believing he also wrote the letter objecting to the Nyingma is not reasonable because the letter objecting to the Nyingma was written with malicious intent specifically against the Nyingma.

Because of the breadth of his experience, if Mikyö Dorje had written that letter, he would have known how people would react. As he understood clearly the pros and cons of writing such a letter, there seems no logical reason for him to have written it.

Apart from the colophon, there is no other evidence to support the view that he wrote it.

Mikyö Dorje was a confident scholar, able to mount arguments and explain philosophical thought. In his other writings, he makes objections. If he had actually written those objections to the Nyingma, he would have admitted it.

Prior to Mikyö Dorje, many other scholars, such as the Sakya Pandita, made well-known, strong criticisms of other schools. There was a tradition amongst Tibetan scholars of the different schools of vigorous back-and-forth criticism. Mikyö Dorje himself once asked the Sera Jetsun to critique his work for him. Within that context, it seems that if he had written such a criticism of the Nyingma, he would not have denied it.

Not long after the letter appeared, Mikyö Dorje denied that he wrote it. If he had written it, the denial seems pointless.

He wrote an in-depth response to the objections, which suggests clearly that he was not their author. He carefully analysed each of the questions and answered them in great detail. The particular explanations he gave were probably of greater help to the Nyingma teachings than harm, the Karmapa suggested.

However, it seems that, in spite of this, later. most Kagyus and followers of the Nyingma spread the idea that the Eighth Karmapa had objected to the Nyingma, and had no knowledge of Mikyö Dorje’s refutation of the objections. Consequently, the controversy has lasted several hundred years. Primarily, this demonstrates that the followers have not taken on responsibility for their teachers.

Why the unfounded allegation about the letter has persisted

The Karmapa suggested there were three main reasons why the fallacy continued.

1. The main reason is that Mikyö Dorje’s response to the objections was not seen by many people. There are three reasons why they might not have seen it:

- Sixteenth century Tibet was not like the modern information era! Even communicating by letter was not easy. Many texts were handwritten manuscripts. The original had to be copied by hand, and then the copies had to be distributed. This was far more difficult than we can imagine. These days we can post something on WeChat or Facebook and within seconds many people will see it. Thus, it is understandable that many scholars of that time saw the criticisms purported to be by Mikyö Dorje but not his response to the objections or explanation.

- Only a year after he wrote his response to the objections, Mikyö Dorje passed away, so he was unable to spread the response to many people, like a drop in the ocean. The fact we can see his response now is that after 1998 many of Mikyö Dorje’s writings were found in the libraries of Drepung monastery and the Potala Palace in Tibet. For over three hundred years, these texts were in a place where no one on the outside was able to see them. It was very difficult for people to read his writings.

- If the letter of objections to the Nyingma was written by someone else, what sort of person would do that? That person was certainly audacious, a scoundrel, who was prepared to appropriate Mikyö Dorje’s name with the intention of offending all the Nyingma and causing a controversy. They would certainly have ensured that the letter was distributed widely within a short time. They may even have tried to prevent the dissemination of Mikyö Dorje’s response, because the more widely Mikyö Dorje’s response spread, the more their letter would lose its effectiveness. Conditions at that time meant that Mikyö Dorje’s letter did not spread widely, and still today, there are very few copies of that text in either pecha or book form, and many people have never seen it. At that time it would have been even harder.

People who had never seen Mikyö Dorje’s response, would readily believe that the letter had been written by Mikyö Dorje when they saw his name in the colophon. They would not imagine that anyone might have appropriated his name. It was complex and full of difficult questions, such as an ordinary person could not write. In particular, people from other schools who were not familiar with Mikyö Dorje’s character, works and activities would take for granted that Mikyo Dorje had written it; they certainly would not have investigated whether Mikyö Dorje had written it or not. For such reasons, as time passed, more and more people believed that Mikyö Dorje must have written the letter. That misconception spread and became the accepted view.

Another reason why people took such an interest in these objections, said to be written by Mikyö Dorje, was that Sokdokpa wrote about them.

The words of the Gyalwang Karmapa,

The omniscient actual Buddha,

The vajra words in good style with a weighty meaning,

Are difficult for ordinary individuals to refute.

Like fire and tinder, they destroy on contact.

He took it for granted that Mikyö Dorje had written it and praised its style, weighty meaning, and strong logic.

Whether or not the letter of objections was written by Mikyö Dorje or not, several of the questions in it raise difficult points, and evoked strong reactions and heated discussions amongst the Nyingma.

For over four hundred years, scholars have written responses to the letter, all the while presuming that Mikyö Dorje wrote it. On the one hand, this shows that there was a lot of affection and partiality towards the Nyingma teachings in the past. On the other it shows that because it had been attributed to Mikyö Dorje it had status. Scholars took an interest in it; they thought it would be influential and wrote many responses.

In conclusion, when we discuss the way of thinking and expression of others, and in particular historical figures, we need to be impartial, calm, methodical, and relaxed. We need to have the motivation and courage to justify and verify things when we research. There’s sometimes the danger of becoming too emotional or getting angry. We have to act in accordance with modern scientific methods, using logic and evidence. It’s similar to debate. On the basis of valid logic of the proof and clear examples and analogies that justify it, we establish what we are trying to prove

It is even less necessary to get angry over it. It’s like watching an action movie: at the time, it seems hot and intense, but actually it’s just a show. It’s not reals. When we do research, not only do we need to use authentic analysis, we must be able to accept others’ explanations of the reasons for how things are, their corrections, and their opinions. If we continue to insist on our assertions without much of a level of education ourselves, speaking with bravado merely for the sake of attracting others’ attention, it’s the talk of someone who always takes short cuts. In terms of logical philosophy, it has no value at all. It is really important that we follow the paths of logic.

The Karma Kamtsang’s connections with other practice lineages

The Karmapa explained that he wished to talk in general terms about the connections between the other Tibetan schools and the Kagyu overall, and with particular reference to the Karma Kamtsang.

The lineage of the Kamtsang explanations of sutra texts goes back to the Sakya school. They were passed down from Rongtön Sheja Kunsik, Jamchen Rabjampa Sangye Pal, his student Karma Trinley Chokle Namgyal and other Sakyas.

The Gelukpa school teaches Mahamudra and the Six Yogas of Naropa according to the Kagyu tradition. Je Tsongkhapa learned these from the Kamtsangpa. Their primary tantric practice is the Guhyasamaja, and they emphasise the explanations of the tradition of Marpa. Their main sutra practice is the lamrim [Stages of the Path] and lojong [Mind Training], which they practice according to the Kadampa school. Other than a few differences in how they explain the Middle Way view and so forth, in terms of dharma in general, the Gelukpa and the Kagyu are closely connected, but a lot of people fail to understand this.

Since the time of Karma Pakshi and Rangjung Dorje, there has been a profound connection with the Jonang school [also known as the Six Yogas school because of the central role the Kalachakra plays]. Most previous Kagyu gurus professed the Shentong view, and later, from the time of Situ Chökyi Jung-le onward, many have taught the Shentong view as it is taught in the Jonang school, so there has been an inseparable connection between the Jonang and the Karma Kagyu which continues to the present day. Likewise, the Shangpa, Shiche, Dorje Nyendrup, and other lineages spread within the Karma Kamtsang around the time of Karmapa Rangjung Dorje. Later through the kindness of Jamgön Lodrö Thaye and so forth, one of the main upholders of those lineages has been the Karma Kamtsang. So there are very many connections between the Karma Kamtsang and other lineages. There is no such thing as a ‘pure’ lineage.

In terms of the relations to the Nyingma, the First Karmapa Dusum Khyenpa’s father was from a Nyingma family. Some say it was his grandfather. His ancestral protector was Rangjung Gyalmo, who thus became one of the main protectresses of the Kamtsang lineage. He received many Nyingma dharma teachings from Chöje Drak Karmowa such as the whispered lineage of the Aro Dzogchen, so the founder of the Karma Kagyu had connections with the Nyingma school.

Second Karmapa Karma Pakshi’s father was also a Nyingmapa, who practised Protector Bernakchen, a practice which had been passed down for thirteen generations of tantric practitioners. This became the protector practice of the Kamtsang. Kathok monastery had been the centre of the Nyingma tantric tradition, and Karma Pakshi received teachings from Kathok Jampa Bum on the Summary of the Intent of the Sutras, Net of Illusion, and the Eighteen Marvels of Mind [three Nyingma tantras that are the basis for the practices of creation phase, completion phase, and Dzogchen].

Karma Pakshi remembered previous lifetimes, and he recalled how, during the times of Indrabodhi, King Ja, and Garap Dorje, he had awakened through the secret mantra teachings of both the Nyingma and Sarma. He then made his main practice the view and meditation of the union of Mahamudra and Dzogchen, the pith instructions on pointing out the crux of the four kayas. He wrote many treatises, including the commentaries on the three types of yoga and wrote in their colophons that his texts might disappear, but the Dharma would never disappear. Because he spent such a long time in Mongolia, most of his works have been preserved in China. In general, there are over one hundred volumes, and it is said that the majority of them are included in Nyingma dharma.

Druptop Orgyenpa was a student both of Karma Pakshi and Götsangpa Gönpo Dorje [founder of the Drukpa Kagyu]. Orgyenpa practised the same level of austerities as Götsangpa. From the age of seven until sixteen, he practised the tantras of Viśuddhe Heruka and Vajrakilaya in the Nyingma tradition. Later, he found some long-life water concealed by Padmasambhava at Chuwo Mountain. He also became the guru of the Mongol emperor.

However, within the current topic, the main point of mentioning Orgyenpa is that he went to India and Uddiyana. Based on his experiences there, he contested the claim by many later scholars that they had not seen Nyingma dharma in India, which threw doubt on its authenticity. Orgyenpa contradicted them. He said that if he were to make a catalogue of all the Sanskrit manuscripts he had seen in India on Dzogchen alone, it would be as long as the Prajnaparamita in 100,000 Lines.

His student was the Third Karmapa Rangjung Dorje, who, of all the Karmapas, had the greatest connection with the Nyingma. He received many Nyingma teachings initially from Druptop Orgyenpa. Then, from Nyedowa Kunga Döndrup, he received transmissions of most Nyingma tantras including Summary of the Intent of the Sutras, Net of Illusion, and the Eighteen Marvels of Mind. While he was at Karma Gön, he had a pure vision of Vimalamitra dissolving into the space between his eyebrows and realised the meaning of Nyingtik, just as it is. Although he had already received the ultimate lineage in terms of pure visions, Rangjung Dorje knew that in our common perceptions, it was important to follow a guru and to receive an authentic lineage that had been passed down from Guru Padmasambhava. The principal holder of the Dzogchen view at that time was Kumaraja, a student of the Dzogchen Mahasiddha Melong Dorje. Kumaraja and Rangjung Dorje had studied together with Orgyenpa, but Rangjung Dorje recognised that Kumaraja was unequalled in his realisation of Dzogchen, so he invited him to Tsurphu and received the cycle of Vimalamitra Nyingtik from Kumaraja.

There are differing accounts of how Rangjung Dorje received the Dakini Nyingtik. This terma, written on yellow scrolls inside a rock, had been revealed by Tertön Pema Ledrel Tsal. According to some accounts, Rangjung Dorje met Pema Ledrel Tsal and was offered the empowerment and transmission from the yellow scrolls. However, the History of Nyingtik by Gyalwa Yungtönpa states that Rangjung Dorje was given the transmission by Lotön Dorje Bum, who had been Pema Ledrel Tsal’s assistant when he extracted the Dakini Nyingtik terma, and does not mention him meeting Pema Ledrel Tsal. This needs further investigation

In his autobiography, Sho Gyalse Lekden, the main student and lineage holder of Pema Ledrel Tsal, relates how Rangjung Dorje summoned him to Kongpo. Sho Gyalse Lekden spent three months there. He gave the transmission of the complete cycle of the Dakini Nyingtig empowerments and initiations to the Karmapa, directly from the yellow scrolls and also received teachings in return. He explains how Pema Ledrel Tsal had given him the yellow scrolls, but he had kept them hidden for ten or eleven years, until he was summoned by Rangjung Dorje.

Rangjung Dorje also had a deep connection with another Nyingma Dzogchen master, Longchen Rabjam, who was said to be the reincarnation of Pema Ledrel Tsal. The two listened to many teachings together.

At the opening of the Questions on Difficult Points, which takes the form of a dialogue between the two, Longchenpa wrote:

Here there is no one else who could dispel the doubts in my mind

Other than the all-knowing one himself,

Whose unified vajra mind is profound peace, great bliss, and spontaneous.

Therefore I have asked these questions.

And at the conclusion, he wrote:

May I, from now until the essence of enlightenment,

Be born in the presence of the Rangjung Guru,

Enjoy the oceanic feast of dharma,

And reach the peace that is free of doubt.

When we see this, we understand that there was a deep and affectionate relationship between the two.

There were many other Kagyu lamas who received Nyingma teachings.

Furthermore, Rangjung Dorje did not just receive Dzogchen teachings; he was also influential in teaching them to others and propagating them widely, in Tibet, China and Mongolia. According to Yungtönpa’s History of Nyingtik

In the first month of the Male Water Monkey, in the isolated place of Tsurphu Dechen, at the request of the great attendant Loppon Yeshe Gyaltsen, he [Rangjung Dorje] transmitted the teachings to five of us—Drongru Khenpo Gyaltsen, Tokden Yegyal, Tulku Önpo Menlungpa, and myself, Yungtönpa. He also gave the five empowerments in full to seven of us, including the shrine master and the tea server, giving us all the instructions in full.

As Rangjung Dorje himself said, “If these teachings of Dzogchen disappear, it will be a great loss, so Yungtön Dorje Pal should spread them in Tsang, Ye Gyalwa in Kham and Kongpo, Yeshe Gyaltsen in Mongolia and China, and Menlungpa Shakya Shönnu should spread them in Ü.” Previously the spread of the Dzogchen teachings had been limited, but now they spread in all directions. The continuation of the Dzogchen teachings was one of the activities of Rangjung Dorje. In brief, the main person to spread the Dzogchen teachings in all directions was Rangjung Dorje, as predicted in the Dakini Nyingtik:

The bodhisattva on the earth

Will spread this to the ocean.

Consequently, he had a lasting influence on the Dzogchen tradition.

Rangjung Dorje’s student Yungtön Dorje Pal was well-versed in the entire sutra teachings, particular the Compendium of Abhidharma [Mahayana abhidharma text by Asanga]. He had received all the Nyingma and Sarma teachings, transmissions and empowerments. He was a student of both Rangjung Dorje and Butön Rinpoche. He had received the complete pith instructions on the three main Nyingma tantras and was very knowledgeable. He wrote the commentary The Illuminating Mirror on the Guhyagarbha Tantra, which became one of the most influential and a source for later commentaries.

The Karmapa related a story. On one occasion, the great Sakya Palden Lama Dampa Sönam Gyaltsen, Dolpo Sherap Gyaltsen, Gyalse Ngulchu Tokme Sangpo—who composed the Thirty-Seven Practices of the Bodhisattva—and Yungtönpa were all gathered together. Dolpopa suggested that among themselves they should show signs of their accomplishment. He began by saying that he had memorised everything that had been translated into Tibetan in the Kangyur and Tengyur. Palden Lama Dampa said he took the four empowerments continuously, ie practised secret mantra without stopping. Gyalse Ngulchu Tokme said he continuously practised bodhichitta and had never lost it. Finally, it was Gyalwa Yungtönpa’s turn. He was a very powerful tantric practitioner, particularly of Yamantaka, so he always carried a skull with him. It was an entire human skull not just the kapala. So he took out this skull that he used daily in his Yamantaka practice and recited a mantra. The skull opened its mouth, bared its fangs, and raced around the room, terrifying the other three scholars. It was an amazing miracle, a sign of the power of his practice of secret mantra.

The later incarnations of the Karmapa all received many empowerments, transmissions, and pith instructions of the Nyingma tradition. Karmapa Mikyö Dorje had many connections with the Nyingma dharma. He had many visions of Padmasambhava while at Tse Lhagang in Kongpo and made a prophecy of an invasion being repelled. He saw that the eight forms of Guru Rinpoche, the eight incarnations of Shang, and the eight incarnations of the Karmapa were inseparable and wrote a Guru Yoga on that called the Shang Kagyama(Sealed Dharma of Shang), or by its full title The Sealed True Dharma of Shang, the Protector of Beings from the Turquoise Cliff. This can be found in his collected works. Although longer, it is very similar to the Kamtsang Four-Session Guru Yoga, which contains the essence of the Shang Kagyama. Also, in his long commentaries on the introduction to the three kayas and the four kayas, he explains the thought according to the Nyingma tradition, and according to the thought of Karma Pakshi.

Many of the famous Nyingma Tertöns were disciples of the Karmapa, so it was even said that it was the Karmapa who had to determine whether a Tertön was authentic or not. Around the time of Situ Chökyi Jungne, terma practices spread widely in the Kamtsang, so probably seventy per cent of the pujas and drupchens in the various monasteries are terma from the Nyingma tradition. The term “Kamtsang Nyingma” has come from this —the union of Kamtsang and Nyingma. The Karmapa suggested that the Nyingma component may be a little stronger. Even within the Karma Kamtsang, the transmission of teachings of the ultimate lineage follows instructions from the Nyingma lineage. Thus, scholars from other schools have suggested that the Kagyu are more knowledgeable about the Nyingma than their own tradition.

When we look at these accounts, we see that the previous generations of gurus and people respected all the other dharma lineages and schools. Not only did they feel close to other schools mentally, but if the opportunity arose, they would take teachings on practice and study from them. If they could serve them, they did.

Our responsibility toward the preservation of the Kagyu lineage

As followers of this lineage, preserving these impressive stories for future generations is our responsibility. But our most urgent and important duty is, as followers of the Kagyu, to uphold, preserve, and propagate the empowerments, transmissions, practice instructions, philosophy, sciences, and history of this lineage. This is because world religions in general and Buddhism in particular are facing a time of change and challenge in our present day. In particular, Tibetan Buddhism is threatened by many internal and external conditions, causing difficulty and harm. So, at this time, it is important for us to work for our own benefit and treasure our own interests, to take care of our own lineages and schools. If we do not take care of our own lineages, no one else will.

Over several hundred years, there has been a great decline in the Kagyu. One reason is that externally there has been political persecution. The Kagyu were ostracised. “There was even a time when we weren’t allowed to play drums or ring bells,” His Holiness declared. “Our communities of practice and study deteriorated, and there was no opportunity to be in an environment where we could study the texts of our own tradition and develop into scholars.”

However, he pointed out, there were also internal factors within the lineage itself. “Our teachings and pure intentions weakened, and many of us did not preserve the fine tradition of empowerments, transmissions, and instructions of our own lineage,” he continued. “We didn’t take any interest. We didn’t take care of the texts and did not study or take an interest in philosophy or other areas of knowledge.” This led to a general defamation of the Kagyu. When speaking of the Kagyu, people in other schools compared them to rodents living in the mountains. “We became an object of scorn for all the other lineages.”

At a time when the essence of the Kagyu seemed about to disappear, many Kagyus are slowly waking up from the sleep of ignorance. “If it is not too late, it is certainly not too early,” His Holiness observed. “We absolutely must search out all the lineages of empowerments, transmissions, and pith instructions that have been passed down from the Kagyu forefathers as well as the old texts, restore them, uphold their lineage and take care of them.” If we can put some effort into it now, there is a chance there may be something we can do, but not if we wait, because within a few decades, there will be nothing left to put our effort into, he warned.

The Karmapa insisted that he was not arguing from a sectarian viewpoint and illustrated his point with an example: how shameful and embarrassing it would be if a Buddhist monk was well-versed in Christianity but knew little about Buddhism. He agreed that it was necessary for life in the modern world to study other world religions and other Buddhist lineages, but our priority should be to study and practise our own tradition to a high level. Otherwise, it would be like cutting down the tree trunk and then trying to hang onto the branches. “Whatever study, practice or activity, we must do whatever we can to put effort into making our own lineage strong and powerful,” he urged. “This is the main commitment or basic responsibility for us as people who follow this dharma lineage.” His Holiness asked that all followers of the lineage think in this way and work cooperatively, with a united spirit, so that the lineage could be preserved.

As the session drew to a close, the Karmapa explained his reasons for spending so much time on the life and activities of Mikyö Dorje. Firstly, he thought it essential to show Mikyö Dorje’s character and to examine the unfounded accusations made for more than four hundred years against him, concerning the letter of objections to the Nyingma. Secondly, he was able to share his thoughts about the deep and profound historical connection between the Kagyu and Nyingma. He expressed the hope that in the future the two lineages could work together cooperatively without any breaches of samaya or controversies, in order to uphold, sustain, and spread their teachings.

In this way, the Karmapa had been able to set the record straight on both these issues.

The Karmapa recounted an incident from his own life which showed how easily misinformation or disinformation could spread.

In 2008, he went abroad for the first time to America and visited California. There, he met one of the sons of Dudjom Rinpoche, Trinley Norbu, who asked him to restore the Tsechu Ritual and Cham. His Holiness was flabbergasted. Trinley Norbu had been told that the Karmapa had stopped the Tsechu Ritual.

“I didn’t know what to say … it has been held continuously from the time of Karmapa Rigpe Dorje!” His Holiness exclaimed.” I wouldn’t even dream of saying ‘Stop doing the Tsechu Ritual.’”

Finally, he reported that in Tibet, some people had been researching Mikyö Dorje’s response to the objections about the Nyingma and had written down some thoughts. This was excellent. The Karmapa concluded that it was important for everyone to work together to establish the truth of events in Tibetan history.