Arya Kshema Spring Dharma Teachings:

17th Gyalwang Karmapa on The Life of the Eighth Karmapa Mikyö Dorje

March 16, 2021

His Holiness began by stating that this was the longest teaching he had ever given. He explained, "Because of the pandemic we are unable to travel so I thought everyone would have time, and also, because of the pandemic, people are turning more to the Dharma with the wish to be liberated from samsara." He had not finished, so he intended to continue his exposition of the Good Deeds next year. To conclude this year's teaching, he would concentrate on aspects of the Great Encampment.

The Eighth Karmapa decreased the pomp and elaborate ceremonies associated with the Great Encampment, and curbed the celebration of Losar. He also declined many invitations from wealthy sponsors in Amdo and Kham. He preferred to stay in poorer regions of Tibet, where there would be fewer opportunities for misdeeds and fewer obstacles to practice. It was a time of many factions and conflicts between the lords of different regions. To live amongst them, he had to be skilled at accommodating them all. He chose to stay in isolated places and mountain retreats in Ütsang, where, generally, there was less fighting or problems. However, many members of his entourage disagreed with his decision and criticised him. They thought:

In Kham and Kongpo, people have more faith in us, and there is more freedom there, so why does he stay in Ütsang, where the officials have little faith and there are few offerings? In both respects, this is a much worse area than Kham and such areas, so why stay? Not only is his activity not flourishing, he also has no freedom and has to accommodate others. He is just making things hard for himself.

Some voted with their feet, deserted the encampment, and returned to their home areas.

The Karmapa reflected on Mikyö Dorje's motivation. His followers accused him of lack of wisdom and being disinterested in furthering the Kagyu teachings. Was this the case? From childhood, Mikyö Dorje demonstrated how very independent and single-minded he was. When the Ming Emperor invited him, even though everyone, including the changzö, insisted he should go, he declined the invitation. He chose to follow authentic gurus such as Sangye Nyenpa Rinpoche. He made firm decisions. Once he was in charge of the Great Encampment, he brought in strict reforms to root out the excesses and misconduct that had grown since Chödrak Gyatso's death. This was a significant turning point for the Great Encampment. During the time of the Eighth Karmapa, the encampment gradually improved and became a thriving centre for the Karma Kamtsang. He established Karma Shungluk Ling, a shedra [for the study of sutra and Buddhist philosophy] and Rigdzin Khachö Ling, a tsokdra [for the study of tantra and ritual]. There were 300-400 solitary retreatants staying in one-man tents. There were also extensive shrines.

It was also a time of burgeoning creativity. In particular, two people, who were said to be emanations of Mikyö Dorje, Töpa Namkha Tashi and Dakpo Gopa Nangso Sidral Karma Gardri, started two new artistic styles: Gardri, "Encampment Painting", and Garluk, "Encampment Sculpture".

Thus, we can see that he was not interested in the external aspects of the Great Encampment or his own aggrandisement. Instead, he worked hard to maintain the traditions of scripture and practice while furthering Tibetan culture. He did not simply follow old traditions though; he started new traditions. Consequently, he was criticised for not keeping the old traditions. Mikyö Dorje maintained that this did not make his activities impure. Because he had to accommodate the needs of infinite sentient beings, he needed different ways in which to tame them, according to the place and time.

In his Instructions for the Lord of Kurappa and His Nephews in the Hundred Short Instructions, he explains his purpose:

Also, if some guides who are sources of refuge benefit sentient beings in ways that do not fit with the examples or manner of dharma practice from their own previous gurus and previous True Dharma, some might say, "These gurus follow examples and dharma practices that do not fit with those of their Kagyu predecessors, so these individuals are impure," and not hold them to be sources of refuge. This is a terribly wrong view. When gurus in their example and methods of dharma practice carry on activity in ways that are incompatible with some aspect of the provisional customs of earlier masters, their activity does not become impure. Sentient beings have infinite different capabilities and inclinations, and in order to tame them, the gurus have inexhaustible examples and methods of dharma practice. Since they tame them in these ways, it is logical to generate even stronger faith and respect for their wisdom, love, and power, because all the gurus'examples and methods of dharma practice are solely for the purpose of purifying the realms of sentient beings.

In order to benefit sentient beings, he reformed things to match a new time and new students, His Holiness commented. Additionally, he was criticised because he described the view of emptiness in a different way from his predecessor. Whereas the Third and Seventh Karmapas had primarily taught the shentong view (empty of other) and the teachings of the Third Wheel of Dharma [the Mind-Only school], Mikyö Dorje primarily taught the rangtong view (empty of self) and, in particular, followed the teachings of Chandrakirti [the Middle Way school —Prasangika Madhyamika]. People said this was inappropriate and wrong. Even among his students, there were different explanations of how Mikyö Dorje explained the view; some said that his view was rangtong, while others maintained it was shentong. Many of his texts, however, emphasised the rangtong view.

Introducing the Karma Gardri Style of Painting

His Holiness first explained his preferred pronunciation of the term Karma Gar-dri. as Karma Gar-ri. In Tibetan, the word dri can refer to calligraphy as well as to drawing and painting, so he found it less confusing to call the painting style Karma Ga-ri; otherwise, when people heard the term Karma Gardri, they might presume it meant a style of calligraphy in the encampment.

The Karma Gar-ri style of painting became an exceptional Tibetan style, developed within the Garchen under the instructions of the Karmapas and their Heart Sons. It emerged as a new Tibetan artistic style augmenting earlier Tibetan art forms with techniques and styles from other cultures. It spread widely and continues to this day.

The Development of Tibetan Art Forms

How did Tibetan art forms develop? They are evident from the 7th and 8th centuries onwards, with the first establishment of the Buddhist teachings in Tibet, when the Tibetan kings founded various monasteries: Rasa, Pekar, Samye, Khamsum Midok and so forth. For example, at Rasa Trulnang Shalre Temple [built c.652 CE], an extant mural bears the words:

Khenpo Gor Yeshe Yang, Gelong Tak Yönten De, and Ge Namkay Nyingpo Yang drew these figures and dharma as merit for the king and all sentient beings.

[The 'king' in question is Songtsen Gampo. He built the temple in Lhasa to house the Akshobhya Vajra image, brought from Nepal by his Nepalese wife, Princess Bhrikuti. The temple was renamed fifty years later as the Jokhang, and remains to this day as the oldest part of a much more extensive temple.]

So, from that time, there was an established tradition of art in Tibet. These days, within Tibet, many modern scholars believe that the famous Jowo Shakyamuni Buddha image in the Jokhang was made in Tibet itself, rather than brought from China by Songtsen Gampo's other wife, the Princess Wencheng of the Chinese Tang dynasty. Similarly, there are carvings done in 804 CE at the Vairochana Cave in Drakyap Ra in Kham, and in 806 CE at Kyekundu in Kham, which can still be seen; they are under the protection of Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche.

Also, during the Tibetan empire, artists began to sign their work. The earliest example is from Dunhuang, a silk painting of the Medicine Buddha and 1000-armed Avalokiteshvara from 836 CE, now in the British Museum. It is signed:

In the Year of the Dragon, I, the bhikshu Palyang, as service for his body, have drawn the Medicine Buddha, Samantabhadra, Youthful Manjushri, 1000-Armed Avalokiteshvara, the wish-fulfilling jewel, and dedications

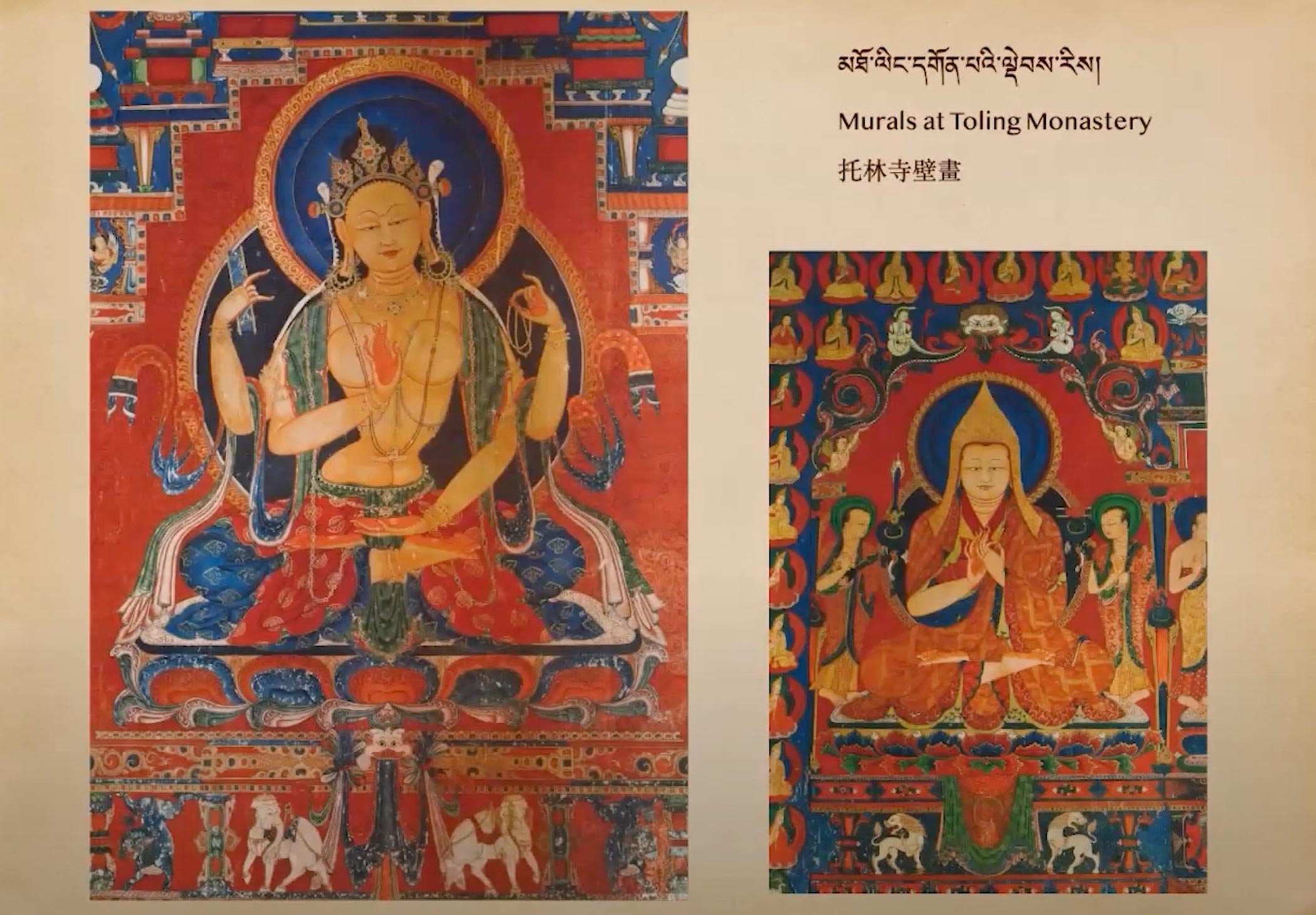

During the time of the later transmission of the teachings, Lochen Rinchen Sangpo (958 – 1054 CE) built several monasteries. He built Toling in 996 CE, and it is still possible to see the murals at Toling. There are also murals at Dungkar Sargo Cave and Wachen Cave. [At this point His Holiness showed two of the murals at Toling monastery, some of which may originate from the time of Lochen Rinchen Sangpo, others later.]

Continuing to give examples of murals that still exist, His Holiness next mentioned the monk Ngönshe, a very famous tertön. He was born in 1012 CE and in 1081 CE, he founded Pal Dratang Monastery. His nephews Jungne and Jungtsul finished the construction in 1093 CE. His Holiness showed photos of an 11th-century mural that has survived there, alongside one from Shalu.

In the 12th century, at the time of the First Karmapa Dusum Khyenpa, there was a famous artist from Ga in Kham called Kyura Lhachen. Although he did complete some paintings, he was primarily a sculptor who made moulded images. One of his works was the statue known as "The Seven Wonders of Dusum Khyenpa", which was at Karma Gön Monastery. It was destroyed during the time of the cultural revolution, but some fragments were rescued and returned to the monastery

At some time after 1263 CE, during the lifetime of Karma Pakshi, the artist and sculptor Pakshi from Phayul was invited to Tsurphu Monastery and made the Buddha statue "Ornament of the World". Cast from copper and brass, it was 13 arm-spans high and the largest cast statue in Tibet. It was such a solid piece that they were unable to destroy it during the cultural revolution. During the 1970s, however, a craftsman visiting Tsurphu realised it had been cast and used fire to smelt it down and destroy it that way.

In the 14th century, from 1306 CE onwards, Shalu Drakpa Gyaltsen painted the murals at Shalu Serkhang.

The Gyangtse Palkhor Chöde monastery was built between 1370–1425 CE, with many different statues and murals. Then, in 1427 CE, Gyangtse Kumbum Stupa was constructed with its extensive murals and statues which can still be seen. His Holiness showed two images of Tara from Gyangtse Palkhor Chöde. These were painted by two artists, Pachen Rinchen and Sonam Paljor, who were teachers of the great master artist Menla Döndrup.

Until the 15th century, most of the paintings and sculptures in Tibet were in either Indian or, primarily, Nepali/Newari style. How then did a distinctive Tibetan art form develop?

Bhikshu Rinchen Chok (born in 1664), from Milk Lake in Gyaltang, Kham, gives an account in a text entitled the Light of the Great Sun: A Commentary on the Presentation of the Characteristics of Bodily Forms Called the Essence of Goodness, which he composed at Tsurphu monastery in 1704. He describes how generally in Tibet, there was the style of the time of the kings, which had spread widely. Then, not long after that, an emanation of Manjushri, Menla Döndrup, was born in Mentang in Lhodrak. At that time, there was a large deposit of vermilion in that region, which was essential for making paints and inks. He was a married layperson but was forced to leave the region because of difficulties with his wife. He went to Tsang, where he studied art from Dopa Tashi Gyalpo. At Dratang, there was one particular Chinese-style painting, and when Menla Döndrup saw it, he immediately remembered his previous life as an artist in China. Using this recall of his previous life, he started using a unique, fully-developed artistic style. Additionally, he determined the measurements and proportions according to the Kalachakra and Samvarodaya, tantras which describe the proportions, costumes and accoutrements of the different deities. This style became known as the Great Mentang style.

Gyalwa Gendün Drubpa, the First Dalai Lama, had a dream that he would meet an emanation of Manjushri the following day, and the very next day Menla Döndrup came to see him. From this the Dalai Lama determined that Menla Döndrup was an emanation of Manjushri. When Gendün Drubpa founded Tashilhunpo Monastery at Shigatse, he commissioned Menla Döndrup to paint the murals of Vajradhara and the Sixteen Arhats. The murals still exist but are very faded, His Holiness commented. A few years ago, a thangka was found at Sakya Monastery in Tibet and on the back it says “painted by Menla Döndrup”. [His Holiness showed photos of the thangka and the inscription written on the back.] Consequently, His Holiness suggested, more research is needed into Menla Döndrup's style and working methods, which became known as the Menluk tradition.

One of his companions and a fellow student of Dopa Tashi Gyalpo was Khyentse Chenmo from Upper Gang in Gongkar. He also developed a particular artistic style which became known as the Khyenluk. His Holiness showed photos of extant murals by Khyentse Chenmo which can be seen at the Sakya Dorjeden monastery in Gongkar. After the break, he showed two more paintings of the Drukpa lineage which may also be by Khyentse Chenmo.

Thus, by the end of the 15th century, the two earliest Tibetan artistic traditions existed, the Menluk [also called Men-ri] and Khyenluk [also called Khyen-ri].

Then came a third, distinctive style developed by Tulku Chiu. He studied art very diligently, travelling around with his paintings and art supplies, studying with various masters. Hence, he earned the sobriquet chiu, which means 'little bird' in Tibetan, because, just like a little bird, he was constantly flitting from place to place. The first part of his name, Tulku, does not mean a reincarnation or emanation in this context but is a title given to artists who make statues and paintings of buddhas and bodhisattvas. He was noted for his superior use of colour.

There were, of course, many other different styles in Tibet, but most of them can be included in one of these three major styles. In his text, the Light of the Great Sun: A Commentary on the Presentation of the Characteristics of Bodily Forms Called the Essence of Goodness, Bhikshu Rinchen Chok describes the origins of these three styles.

Lord Sangye Gyatso's Catalogue of Offerings of the Ornament of the World, written in 1697 CE, is the primary source for historians of Menluk and Khyenluk. It mentions Dopa Tashi Gyalpo, his students Menla Döndrup and Khyentse Chenmo, and the Chiu style. However, there is not a single mention of the Gardri style. The reason for this is unclear, but Sangye Gyatso was writing at a time when the Karma Kagyu were being suppressed, so mention of the Garchen would also be suppressed.

Geshe Tenzin Phuntsok of Marshö Gojo [born 1673] was skilled in Tibetan medicine and astrology. He also wrote about techniques of colouration in a text called Giving Hues to Flowers and Bringing Out the 100,000 Colours of Rainbows. In this work, he wrote a history of Tibetan art similar to that of Sangye Gyatso. In 1716, he wrote the Long Explanation of Consecration: The Smile that Pleases Maitreya, Eight Parts of Excellent Auspiciousness. This again reiterates what Sangye Gyatso wrote about "the three great styles".

The Development of the Gardri Style

The first text to speak about the development of the Gardri was the Light of the Great Sun: A Commentary on the Presentation of the Characteristics of Bodily Forms Called the Essence of Goodness. Its author was Bhikshu Rinchen Drupchok from Gyaltang, who, as a boy of eight or nine, met Karmapa Chöying Dorje.

Many modern art historians who have researched Tibetan art say that Karmapa Chöying Dorje was one of the most important Tibetan artists. In the earlier part of his life, he painted in the Menri style, then later in life followed the Kashmir style and the Chinese style. He melded these two styles into his own unique technique for drawing figures and colouration. His work is very distinctive. When you see it, you know immediately that it is the work of Karmapa Chöying Dorje.

When the young Rinchen Drupchok met Karmapa Chöying Dorje, the Karmapa told him to draw images of the Buddha. The Karmapa consecrated them and predicted that in the future, Rinchen Drupchok would become skilled in drawing and painting and become a great artist. Later, when Rinchen Drupchok reached the age of 20, the Sixth Gyaltsap Norbu Sangpo told him, "There is no one else who is continuing the Gardri style, so this is a very difficult situation for the Gadri style…other than Tulku Awo Netso, no one is painting in the Gardri style, so you must go and study painting with Tulku Awo Netso."

At the time of the Eighth Karmapa, there was a student of Könchok Pende (a contemporary of Namkha Tashi), called Yangchen Tulku Töpa. He was an attendant of the Sixth Shamar Chökyi Wangchuk. It was said he could remember seven former lives during which he had been an artist. In particular, in his previous life, he had been Cha Netso, a parrot (Tib. netso means "parrot"; cha netso means "parrot bird"), and he had heard many teachings on painting from the Fifth Shamar. Because of the imprints from that lifetime, he remembered them from an early age, and he was nicknamed Tulku Awo Netso. He lived to the great age of 71. However, no one had been taking care of him, and he was having a very difficult time, So Gyaltsap Norbu Sangpo sent supplies of food and clothing. Rinchen Drupchok spent nine months studying art with him and learnt the fundamentals of the Gardri style. Not long after that, the teacher died.

Later, another artist, named Tsepel, encouraged Rinchen Drupchok to write about the Gardri style and proportions. Subsequently, seven years later, he wrote the Light of the Great Sun: A Commentary on the Presentation of the Characteristics of Bodily Forms Called "The Essence of Goodness". This was in 1704 CE when he was 41 years old and staying at Tsurphu monastery. His Holiness said that no one knows who wrote the root text, The Essence of Goodness, so it is essential to continue to search for it. Rinchen Drupchok's commentary gives the proportions of the Gardri style and is the earliest and most respected source. His Holiness stated this text is one that all Gardri school artists should study and research.

Awo Netso is mentioned in the collected works of the Thirteenth Karmapa:

During the time of the Fifth Karmapa, Könchok Yenlak,

There was one named Netso,

Who later became a monk called Tulku Awo Netso,

He became known as skilled in art.

His Holiness commented, "During the time of Könchok Yenlak, there was Awo Netso, a parrot. That parrot had a very nice voice, and later, in the next life, he became a monk and an artist, and so he was called Tulku Awo Netso."

Rinchen Drupchok's commentary, the Light of the Great Sun contains a detailed history of the Gardri tradition. His Holiness paraphrased the text with additional comments:

Now, what is our own tradition? In the Gardri style, there is Tulku Namkha Tashi; he is the one who founded the Gardri style. Tulku Namkha Tashi was born in the region of Yartö. When he was a young child, Mikyö Dorje said that he was his own emanation. Not only did he say that he was his own emanation, but said that he would perform the activity of his body, so that Namkha Tashi would have the intention of engaging in artistic activity; that is why Mikyö Dorje recognised him as an emanation. He put him under the direction of Shamar Könchok Yenlak.

There was also a fortunate easterner called Könchok Pende from the region of É. Regarding this region of É, there were many artists who came from that region, particularly many painters. Many of the greatest painters in Tsang came from the region of É. It was said that Könchok Pende was an emanation of Gyasa Kongjo—the Chinese call him Wong Chong Kung.

Namkha Tashi was put under the instruction of Shamar Könchok Yenlak, and Könchok Pende was put under the instruction of Gyaltsap Drakpa Döndrup. These two together used the Indian lima tradition of painting and the previous Tibetan Mentang tradition as a basis, and drew landscapes with colouration like Sitang during the time of the Ming emperors. During the time of the Fifth Karmapa, Deshin Shekpa and the Chinese emperor, Yongle, there were many wondrous events, and these were drawn in a painting. There were two copies of this painting. The emperor himself kept one, and one was given to the Karmapa, and then to the monastery at Tsurphu, and is still extant today. That painting shows the Ming style. Namkha Tashi and Könchok Pende used this style of painting from China, and they developed the artistic style called the Gardri. Likewise, there was an expert sculptor called Karma Sidral, nicknamed "Crazy Go", and he had a student Po Bowa who was also said to be an emanation of the Eighth Karmapa. There were many other people, such as Karma Rinchen, who were experts in this style of sculpture, but by the time of Rinchen Drupchok, this style of sculpting had already disappeared. So, at that time, there was not a lot to be seen.

His Holiness continued that although Namkha Tashi is generally credited with founding the Gardri style, he was working with Könchok Pende as well, so they should both be credited as founders of the style.

More recently, the main source that is used for the history of the Gardri style is Jamgön Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye's Treasury of Knowledge. It reads:

There was Tulku Namkha Tashi from Yartö. Mikyö Dorje said that he was his own emanation and would propagate artistic activity. With instruction from Shamar Könchok Yenlak and Gyaltsap Drakpa Döndrup, the fortunate easterner Könchok Pende from É studied the Menluk style from Gyamo Sa Konjo's emanation. Using the proportions from the Indian limaand Mentang traditions as a basis and drawing landscapes with colouration like Sitang from the time of the Ming emperors, this became known as the Gardri style.

Once more, His Holiness emphasised that Tulku Könchok Pende should be credited as well as Namkha Tashi.

Finally, he pointed out that although many people paint in the Gardri style in Tibet these days, there are still many blank areas in its history. It was, therefore, important to clarify the topic of the Gardri style by identifying the Gardri style of painting and proportion, and differences between the original and the modern style.

Click the photo to view photo album: