Hotel Anand International, Bodhgaya, Bihar

24-26 February, 2016

“It is of great concern to me that over the last sixty years so much of the priceless heritage of Tibetan Buddhism has vanished, not just through theft and deterioration, but because of lack of knowledge and skill in preservation. Over the last twenty years alone far too many irreplaceable works of art such as thangkas, statues, dance costumes, texts, and other sacred artifacts have been lost to future generations.”

– His Holiness 17th Gyalwang Karmapa

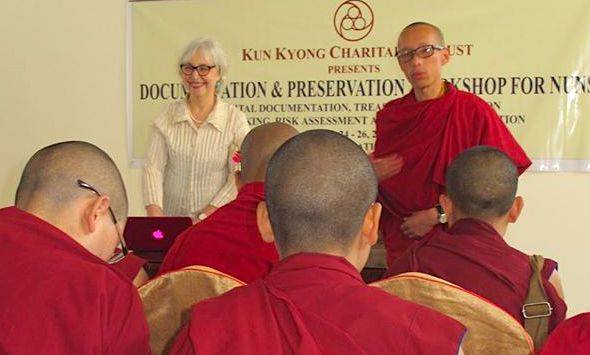

At the request of the Gyalwang Karmapa, a group of 17 nuns representing all eight Karma Kagyu nunneries completed an intensive three-day training to learn techniques for documenting and preserving the treasures owned by their nunneries, such as statues, thangkas, and texts. In addition, the nuns learned to interview and video-document elders about the history and significance of various treasures; the elders are in many cases the sole holders of this knowledge. The training took place at a hotel close to Tergar Monastery in Bodhgaya, following the completion of the Kagyu Monlam.

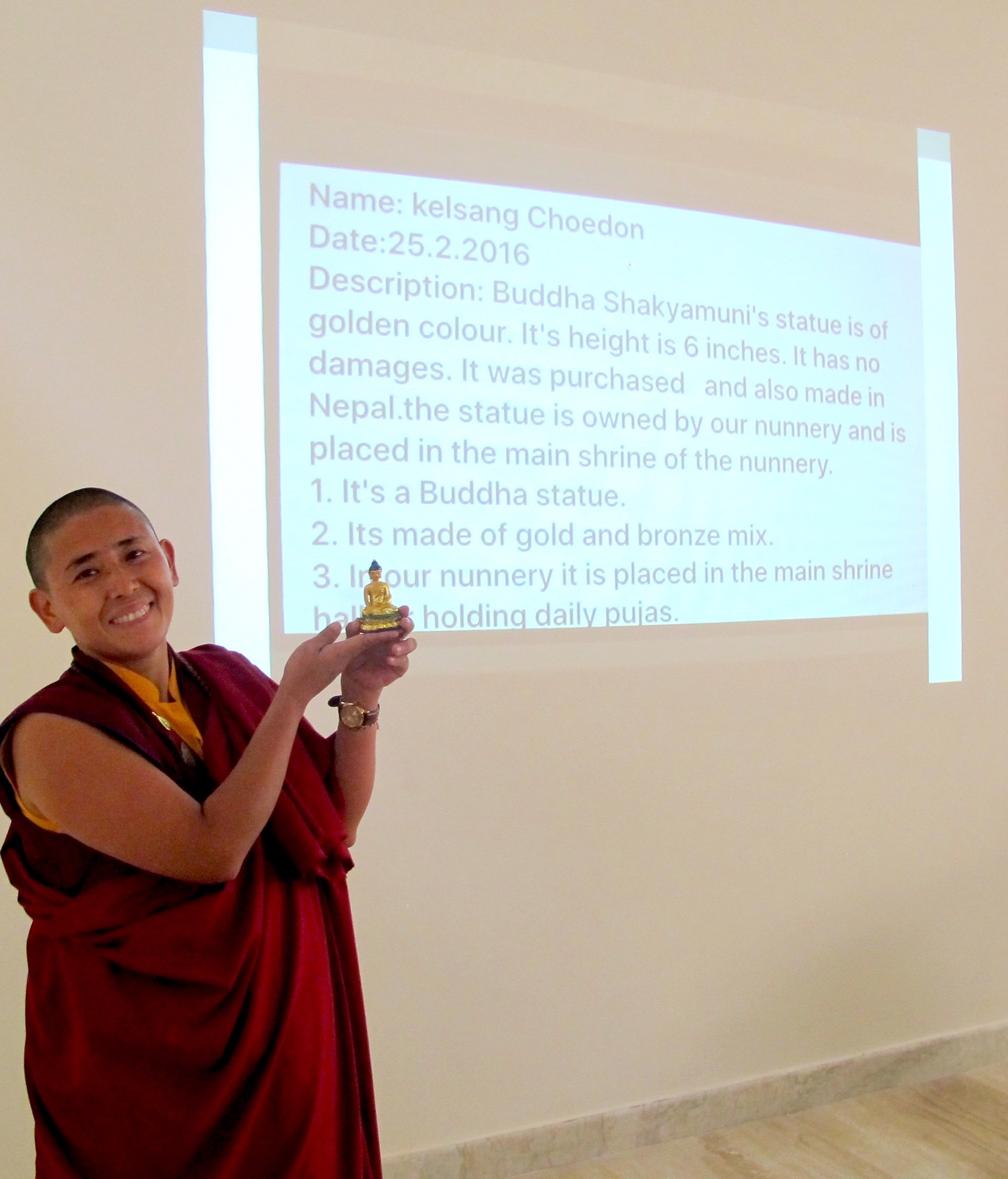

The program was organized and funded by the Kun Kyong Charitable Trust, of which the Karmapa is the primary patron. The trust began offering annual workshops for nuns last year, with the aim of teaching them skills that will help them to uphold the dharma. Last year’s workshop was on communication and leadership. An emphasis in this year’s training was also preparing the nuns to teach and share the information on treasure preservation with others at their nunneries. For example, two or three nuns were required to present their work after every group activity. Even over three days, the nuns’ confidence in standing up in front of a group and giving a presentation improved dramatically.

The director and lead instructor of the training, Ann Shaftel, became an expert in sacred art preservation at the advice of the 16th Gyalwang Karmapa, who told her “preservation of Buddhist paintings and statues is your Dharma work for this lifetime.” That advice propelled Shaftel to receive two graduate degrees and to eventually hold advanced international standing in the field of Art Conservation. During this time she has worked with dozens of monasteries and art museums to preserve sacred Buddhist tangible culture. She also developed this Treasure Caretaker Training—normally offered as a 10-day workshop—for training monks and nuns to become leaders in the preservation of their monastery collections.

One of the main skills the nuns learned in the training was how to create digital documentation of all the treasures in their nunnery, including those in shrine rooms and storerooms. This means taking photographs (using their mobile phones) and creating notes regarding condition, dimensions, artist, how it is used in the monastery, and other details, for each piece. This information can be used to create a digital inventory, which most monasteries do not yet have. In the case they have difficulty getting access or using the technology, Shaftel also taught the nuns how to draw images and take notes on paper about each piece. “Better to have some documentation than no documentation,” she told them. However, with mobile phones being fairly ubiquitous now, and the hands-on experience they received through the training, the nuns seemed eager and capable of creating digital documentation at their nunneries.

Notably the favorite part of the workshop for the nuns was learning how to interview elders about their treasures. The nuns took turns interviewing each other about their precious treasures (imagination was involved), while filming each other with their phones. Part of the interview training included making the elder comfortable and offering tea, and making sure to get their permission to film and share their stories. While this part of the workshop involved much laughter and fun, the training is critical for saving many stories passed through an oral tradition regarding the history and meaning of many sacred artifacts.

The nuns also learned practical tools for preventing damage and deterioration of the treasures in their storerooms. In particular, they learned about how to protect thangkas, texts, and other sacred objects from getting damaged by humidity, light, insects, and other factors. This knowledge is crucial for the nunneries that experience the monsoon season, when mold and humidity can create major problems for old texts and paintings. The nuns also learned labeling techniques. While it seems simple, many monastery storerooms lack proper labels, which can make things difficult to find. Without labels, certain objects can also be mysterious when found, if there is no documentation about what it is or where it came from and the oral history has been lost.

One of the topics Shaftel emphasized in the workshop was the importance of confidentiality. In the past, monasteries often avoided creating treasure inventories because of security issues; the reasoning being that if others knew what they had in their storerooms they would be at greater risk for theft. However, not having an inventory puts treasures at risk in other ways. For one, pieces can go missing with no one noticing. And during times of natural disaster or political upheaval—such as the recent earthquakes in Nepal—inventories help storeroom keepers to make sure nothing gets left behind or lost. Having an inventory also helps with organization; knowing where a precious thangka is in a storeroom helps one avoid digging through an entire box of thangkas looking for one, which damages the fragile paintings and fabric. The digital images can also aid in conservation, or re-creation, of the artwork in the future.

On the final day of the workshop, the nuns’ were delighted by a visit from Karmapa’s sister Chamsing Ngodup Pelzom, who offered some words of advice:

In all Buddhist traditions, it is said that we should not lean on others, but stand on our own two feet and walk along our path. Many of us have little education and come from small villages, but that should not stop us from trying to do whatever we can… to take advantage of whatever opportunities present themselves so we can become a model for others. A few nuns can make a big difference. You’ve received training, learned it well, and when you go back to your nunneries you will teach it to others so hundreds will benefit.